In recent weeks, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is back in the news. TPP aims to lower barriers to trade among the United States and a variety of other nations including rich countries like Japan, Canada, and Australia and developing countries like Chile, Peru, Vietnam, and Malaysia. US Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) has come out strongly against TPP, as has senator and presidential candidate Bernie Sanders (D-VT). President Barack Obama continues to support TPP–he recently succeeded in having the agreement fast-tracked by the senate and will likely replicate that success in the house. Once TPP is fast-tracked, congress cannot debate the treaty’s contents or make amendments to it. Is TPP good for the United States? Who is right?

The first thing that must be pointed out is that we don’t know what TPP does for certain. The details of the treaty have not yet been disclosed to the public, and those who have had the opportunity to read through TPP have not been permitted to discuss the contents in detail. I can share with you the general concerns that people have and I can discuss the theory surrounding free trade agreements, but I cannot do a line by line analysis at this time.

So here are the specific core concerns we’re hearing about TPP from Warren, Sanders, and others:

- Job Losses and Wage Suppression–past free trade agreements between the US and other countries have sometimes resulted in US job losses and slower wage growth, and there are fears that this will happen again with TPP. So far, the research the Economic Policy Institute has been able to do seems to support these concerns.

- Dispute Resolution Courts–TPP will allegedly require impartial third party courts to force signatories to obey its provisions. These courts will enable foreign corporations to challenge US laws and win payouts from the US government and they are not subject to US judicial oversight. This could undermine US labor laws, food safety standards, or environmental regulations.

- Disallowing Capital Controls–TPP will allegedly prevent governments from using capital controls to restrict the flow of money into or out of their economies, reducing the ability of the government to effectively respond to economic crises.

This sounds potentially worrisome, but Obama and the proponents of TPP claim that free trade is good for economic growth and that Warren and Sanders are either fear mongering or trying to resist globalization, which they deem a foolish and futile endeavor. They argue that attempting to avoid international competition will only serve to make the American economy less competitive. There are a lot of contradictory claims being made, and without the text of TPP, it is very hard to get a handle on what is fact and what is fiction. Since we cannot get more specific about TPP, let’s get more general–let’s clarify our thinking about how free trade affects economies differently in different contexts. As I see it, there are three types of free trade agreements:

- Textbook Free Trade–where both countries genuinely do benefit from the agreement.

- Exploitative Free Trade–where a richer country uses a free trade agreement to exploit a poorer country.

- Submarine Free Trade–where a poorer country tricks a richer country into a free trade agreement that bleeds the richer country and feeds the development of the poorer country.

Let’s discuss each of these in turn.

Textbook Free Trade (TFT):

This is the sort of free trade agreement an undergraduate economics student is likely to read about in first semester. Broadly speaking, there are two situations where TFT can happen:

- Different Specializations–if Canada is great at making oil but awful at making olives and Italy is great at making olives but awful at making oil, both Canada and Italy are better off if they can freely exchange oil and olives. This allows each country to specialize rather than divert resources and energy to making products for which they are not well-suited. TFT in this situation leads to more total production of goods in both countries, creating jobs on both sides. Everyone wins.

- Fair Competition–both Japan and the United States make good cars and both have similar labor laws and wages. If they compete with each other, each is forced to try harder to make better cars, resulting in faster improvement in car technology in both countries. Since both Japan and the US automotive industries are competitive, neither gets wiped out and consumers on both sides get better products for less money. Again, everyone wins.

The problem is that many people assume that all free trade agreements are TFT. As a result, free trade agreements don’t get scrutinized as much as they should and countries often fall into exploitative or submarine free trade.

Exploitative Free Trade (EFT):

Historically, empires have ruthlessly engaged in EFT, using their power to force other states to accept free trade in contexts that massively favor the powerful state at the expense of the weak one. The British Empire was spectacular at this. In The National System of Political Economy, Friedrich List went into a great deal of detail about how the British Empire used free trade to strengthen its own industry at the expense of other European countries during its rise.

Here’s how the strategy works. Let’s say a country gains a large advantage in some industry. In the British case, textiles are an excellent example. Britain came to possess superior textile infrastructure, technology and expertise, such that even if another country were geographically better situated to make textiles (e.g. if it was a good country for growing cotton, or making wool, silk, or some other fabric), that country would struggle to get a nascent textile industry off the ground because it lacked the infrastructure, technology, and know-how possessed in Britain. In this situation, the only way to create a textile industry that could compete with Britain’s was to completely shield the nascent industry from British competition. Britain knew this, and so when it began to see an industrial rival emerging, it would attempt to persuade the other government to go into a free trade agreement. Britain would offer to import a large amount of that country’s agricultural products if that country would import British manufactured goods in return. The British negotiators would claim that this was a classic case of TFT under different specializations, and the other country’s government would usually come under significant pressure from the agricultural interests (typically led by nobles who had considerable political power) to make the deal. Britain was happy to buy French wine if it meant that France would not become competitive at making textiles or warships. The French landowners made money off of these deals even as they damaged France’s future as a potential world power. In the short run, both France and Britain made money off of these deals, but in the long run they massively favored Britain. Or, as List put it:

The nation must sacrifice some present advantages in order to insure to itself future ones.

No country today enjoys the kind of industrial advantages that Britain had in the 18th and 19th centuries, but we still see EFT today. The free trade we see in the Eurozone could be accused of being EFT by many people living in countries like Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece. They might see the EU’s free trade system as a tool by which Germany perpetuates and sustains competitive advantages over the EU countries in the periphery. But that’s a subject for another post (like this one, which I wrote in April 2013). Today, we’re seeing a lot of submarine free trade, which would have been unthinkable half a century ago.

Submarine Free Trade (SFT):

In SFT, a weak country uses the fact that it is underdeveloped to its advantage, leveraging its backwardness to undermine the economic success and development of a powerful state. This is a recent phenomenon–it only really began to happen beginning in the 1970’s. China is amazing at it. Here’s how it works.

When industrialization was new, a country needed to have the most advanced technology to do it competitively. As time has passed, the gap in industrialization between the affluent countries and the rising economies has become smaller than it used to be. Because of the relative strength of labor laws in affluent countries like the US or the UK, countries like China can be a bit technologically underdeveloped but still remain highly competitive by effectively turning their workers into 19th century style wage slaves. Chinese workers take the jobs because even with negligible pay, they are still marginally better off in the factories than they are on traditional Chinese farms. In this kind of situation, free trade between the US and China will allow American consumers to buy goods at lower prices, but it places a massive anchor around US wages, making it very difficult for wages to rise without ceding more jobs to China. In the short term, the deal still looks like a win-win–Chinese workers get slightly better (albeit still quite miserable) jobs, while American workers get cheaper products. But in the long-run, SFT utterly devastates America by crippling wage growth. Trade with China is not the only cause of US wage stagnation, but it has played an important role. Since Nixon opened China in the 1970’s, US inflation-adjusted wages have hardly budged:

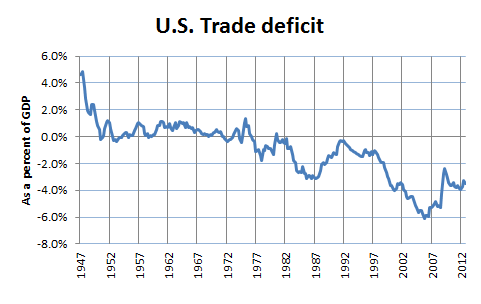

Trade is not the only cause–during this period, minimum wages have fallen, unions have been weakened, regulations have been relaxed, capital controls have been rolled back, and so on. But many of these policies have been motivated in part by a desire to remain competitive with China and other poorer countries. This invariably entails suppressing wages. It hasn’t really worked–since the end of the Cold War, the US trade balance has become quite negative:

Without wage growth, it becomes very difficult for a country to sustain growth in consumption. To make up for it, countries often resort to excess lending, leading to bubbles which eventually burst, hemorrhaging economic growth. The short term boost in cheap imports America enjoyed came at the high price of stagnant wages, excess borrowing, and an unstable economy prone to bubbles.

As for China? It’s in an odd situation too–because its workers earn so little money, they can’t provide enough domestic demand to keep China’s economy afloat. If China raises wages to create a sustainable domestic economy, it will lose jobs to the US and Europe or to other rising countries. But if China doesn’t raise wages, it will remain dependent on continued growth in the US and Europe, and this growth is being stymied by the wage stagnation caused by trade with China in the first place. In effect, China acts like a parasite on the US and Europe, using them to feed itself and depleting the source of its strength in the process.

How do we resolve the dilemma posed by SFT? Here are a few possible outcomes and solutions:

- Automation Revolution–if the US and Europe can leverage their technological superiority in time to create a heavily automated industrial economy dominated by robots, they can regain the large technological advantage they previously enjoyed, consigning the wage slavery model to the historical dustbin. The problem is that the more manufacturing we do in low wage countries, the less stake international corporations have in American and European manufacturing and the less incentive there is for American and European countries to develop automation technologies. Affluent governments may need to make investments in this area to make up for that disinterest if they wish to regain dominance.

- Chinese Superpower–if the affluent countries weaken at a slow enough rate, China may be able to develop fast enough to develop a sustainable domestic economy or to acquire a sphere of influence allowing it to maintain its economy with less reliance on the US and EU. China would then become a serious rival of the US and EU, though it is unlikely that China would be able to continue developing rapidly beyond that point–it would likely soon fall victim to other rising countries with very low wages and join the US and EU in their malaise. Over time, these subsequent low wage economies would go through the same rapid rise China went through, until eventually the entire world would be developed to a roughly similar extent, at which point all countries would have similar wages and fair competition would once again become possible. Alternatively, it’s possible that after China rises, it could achieve the aforementioned automation revolution and become the premier power on the planet.

- General Collapse–if the affluent countries cannot sustain China’s growth for long without further economic crisis, their rapid decline would prevent China’s rise, leading to a nightmare scenario where mutual dependence inflicts ruin on all of the economies in play.

- Protectionism–the affluent countries could pass protectionist laws preventing low wage economies from competing with them, possibly splitting the global economy into two subsystems, one running on high wages and strong labor laws and another running on wage slavery. This is unlikely because it would severely undermine the business models of many transnational corporations that have significant political influence on both sides of the Atlantic. It would also make it much harder for poorer countries to develop, as they would no longer be able to use rich foreign consumers to make up for weak domestic consumption.

- Wage Cartel–countries could club together and sign an international treaty fixing international minimum wages and labor laws and denying countries who refuse to sign access to global markets. This runs into many of the same problems as #3–it could cleave the global economy in two and would face massive resistance from those who profit from the current model. Additionally, if the poorer countries were to sign on, it would trap them in poverty indefinitely, as the affluent countries would almost certainly use EFT to keep them down.

- Neoimperialism–the rich countries could go to war with the poor countries over labor laws, but because of the existence of nuclear weapons this cannot happen without countries exposing themselves to the risk of nuclear holocaust. This would also contravene the interests of transnational corporations.

In effect, #4, #5, and #6 are all strategies the rich countries could use to preserve their power and advantages, but in each case they are likely to be stymied by transnational corporations that are indifferent to the international balance of power and seek only private financial gain. #1 would allow the reemergence of the rich countries without upsetting those vested interests, so it is a realistic possibility. If automation doesn’t happen, we are left wondering whether it’s going to be #2 or #3, both of which result in more global equality, but at the expense of the prosperity and growth that has been enjoyed for so long by Americans and Europeans.

What kind of trade deal is TPP? Free trade among the affluent countries, all of whom have significant labor laws and respectable wages, is likely to be textbook, with advantages mutually enjoyed. But free trade among countries with very different wages or labor laws will produce the submarine effect in today’s context. Because TPP contains a number of affluent and rising countries, there will likely be a mix of both. If we were to reject TPP, this would be a move in favor of protectionism or perhaps, more ambitiously, a wage cartel, but because of the influence of moneyed interests on democratic politics, it is unlikely that TPP will be rejected or that its rejection would result in any broader movement to change course. Some worry that these countries might respond to a rejection by moving into agreements with China and entering its sphere of influence voluntarily, but this is unlikely because China is in located in Asia and poses a much greater long-term threat to most of these other countries than the US does.

If you’re an egalitarian living in an affluent country, you have an interesting choice to make–do you care more about equality within your society, or do you care more about global inequality between rich and poor states? The very policies that mitigate the latter exacerbate the former. Allowing countries like China to develop weakens our societies and creates inequality and poverty at home. But using automation, protectionism, or war to stop the suffering at home also condemns people living in poor countries to continued technological backwardness and poverty. Should it be us or them?