In recent weeks, I have had the very same conversation with a number of my friends. Each time I’m told that they were participating in a discussion about the minimum wage when someone claimed that there was no point in raising wages because firms would just raise their prices to cover the increase. This is a very intuitive, appealing argument, but it’s deeply misleading and fallacious. Let me explain why.

If minimum wage hikes automatically resulted in price increases, we would expect to see the inflation rate rise whenever the minimum wage rises. This does not happen. Here’s the US federal minimum wage since 1938:

The green line shows the raw minimum wage. The red line shows the real value of that wage when you take inflation into account. Here’s the inflation rate over the same period:

There is no clear relationship. The minimum wage more than doubled in inflation-adjusted value between 1948 and 1968, but inflation during most of this period was stable. From 1968 to 1988, the inflation-adjusted value of the minimum wage actually fell by around one third, but inflation still spiked throughout the 70’s. In 2008, the minimum wage saw its largest increase in decades in both real and nominal terms, but inflation not only failed to rise, it cratered.

Indeed, the very fact that you can raise the inflation-adjusted minimum wage at all shows that this argument is completely false. If minimum wage hikes were entirely offset with price increases, it would not be possible to raise the inflation adjusted minimum wage from $4.07 to $10.56, but this is precisely what happened between 1938 and 1968. Instead, the blue line would simply be flat, or at the very least it would rapidly re-converge to some flat trend line. The graph looks nothing like this, which suggests that this argument is fundamentally broken in a basic way.

What’s wrong with it? It relies on the assumption that firms pay their workers the maximum amount they can possibly pay while staying in business, such that any increase in wages necessitates raising prices. This could not be further from the truth–firms do not try to maximize wages, they try to maximize profits. To maximize profits, firms need to minimize their labor costs, not maximize them. So firms try to pay their workers as little as they can get away with. Historically, the minimum a worker could be paid was traditionally the subsistence wage–the amount of money the worker needed to buy food and pay rent, i.e. to subsist. Over the last couple centuries, wages have risen above the subsistence level for three core reasons:

- Scarce Skills–many firms now need skilled workers. There are often fewer skilled workers than firms need, and this means that firms must compete for skilled workers by offering them higher wages. So skilled workers have more bargaining power than unskilled workers (provided that the specific skills the worker has are in high demand).

- Trade Unionism–governments have legalized unions and created union rights. Collectively workers have more bargaining power than they do individually, and this allows them to negotiate higher wages.

- Minimum Wages–governments have set floors on wages above the subsistence level to increase the purchasing power and standard of living of workers.

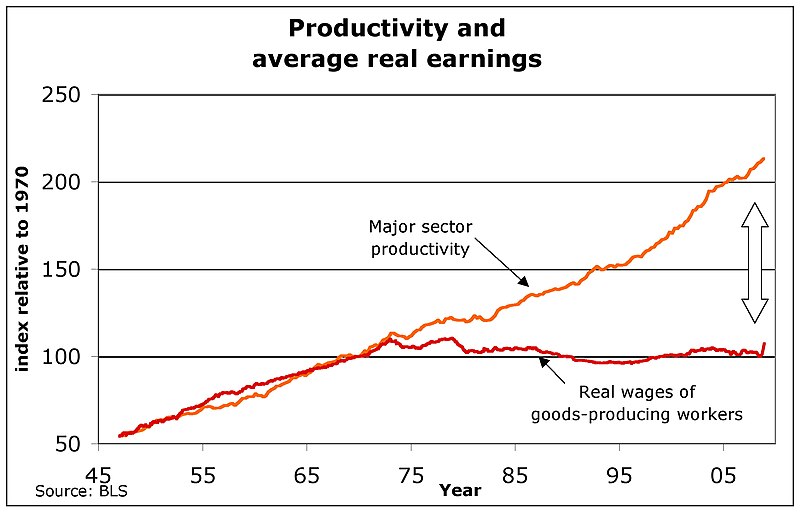

If firms were always paying as much in wages as they possibly could without raising prices, trade unions and minimum wage laws would be completely ineffective at raising inflation-adjusted wages. But history shows that the opposite is true–when unions were strongest and the inflation-adjusted minimum wage was the highest (roughly the thirty year period between 1945 and 1975), inflation-adjusted wages grew continuously alongside productivity. But when the inflation-adjusted minimum wage stopped rising and unions were weakened, wages stagnated while productivity continued to rise:

In truth, when workers’ bargaining power increases, firms are forced to eat into their profit margins, but they do not necessarily respond with price increases. Right now, US corporate profits as a percent of GDP are at an historic high:

These large profit margins make it easier for firms to raise wages without raising prices. Firms also have strong competition reasons to avoid price increases. If the minimum wage rises and McDonald’s decides to raise prices, Burger King may be able to capitalize by keeping its prices down. Customers may defect from McDonald’s to Burger King. This would allow Burger King to make more money than it did before, and it would certainly allow Burger King to eat into McDonald’s market share. McDonald’s cannot know whether or not Burger King will try this strategy, and this gives McDonald’s strong reasons to keep its own prices down. For these reasons, you’ll find that the cost of a Big Mac has little to do with the size of the minimum wage:

We can see that the difference between the US minimum and the minimums in other countries does not produce a corresponding difference in Big Mac prices. It is very possible to significantly reduce the number of minutes a minimum wage worker would have to work to pay for a Big Mac. In some cases Big Macs even cost less in countries with higher minimum wages or more in countries with lower wages. Here are a few of the most interesting cases from the above figure in chart form:

|

Country |

Minimum Wage Difference Compared with US | Big Mac Difference Compared with US |

| Australia | $9.41 |

$0.64 |

| Brazil | -$5.27 | $1.48 |

| Canada | $2.00 | $0.43 |

| France | $4.84 | $0.23 |

| Greece | -$2.19 | $0.23 |

| Japan | $0.92 | -$0.04 |

| New Zealand | $3.93 | -$0.15 |

| UK | $2.58 |

-$0.38 |

Even if you or someone you know doesn’t find this argument persuasive, we have demonstrable evidence that firms do behave this way. Remember, if firms really did raise their prices to fully compensate for wage increases, it would never be possible to increase inflation-adjusted wages. The 45′-75′ period shows that this is definitively not the case–real wages can rise, and this means that wages can rise without inflation. It is possible to have an economy where a minimum wage worker has to work only 18 minutes to buy a Big Mac as opposed to 35. These economies exist and have existed.

Are there situations in which a wage increase would trigger price increases? Yes. If corporate profit margins were small, firms would have no choice but to raise prices. Alternatively, if the economy were producing at capacity such that increased consumption resulted in shortages, prices would have to rise to prevent demand from outstripping supply. But we are in neither of these situations. Instead, we are in the opposite kind of situation–corporate profit margins are very large, and there is not enough demand for goods and services to support full employment. By raising wages, we can transfer excess profits to consumers, allowing them buy more goods and services. This would signal to firms that they could produce more goods and services at a profit, and that will encourage firms to increase production and hire more full-time workers. That would kick the economic recovery into a higher gear. When wages have risen sufficiently, we should see corporate profits return to normal levels and full employment.