On August 27th, Bernie Sanders decided to come to West Lafayette, Indiana, to do a town hall. Indiana is my home state. Bernie is 79. This could be the last time he visits, for all I know. My girlfriend is a few years younger than me. She’d never seen Bernie in person. We decided to drive down. Let me tell you the story.

The town hall was scheduled to start at 6 PM, with doors opening at 5 PM. When you go to see Bernie, there are always two “waits”. The first wait is the wait outside the venue. Bernie tends to fill his venues to capacity, even now, and you have to come early to get a seat. It’s hard to be sure how early. I remember going to see him in Chicago and queuing at 2 PM for an event that didn’t start until around 7 or 8. I remember going to see him in Cambridge and queuing up at 4 AM for an event that didn’t start until 9 or 10. We didn’t want to take any chances, so we drove by the Tippecanoe County Amphitheater Park at 1 PM, just to see if anybody was there yet. It was still deserted, so we came back at 3 PM. At this point there were a few hardcore Bernie people in the parking lot, but still lots of room. We ended up coming back again shortly after 4 PM, and that’s when we decided to line up.

The “line” was more of a scrum than a line, and the organizers weren’t sure whether they were going to allow people to bring in purses or bottles of water. Ultimately they decided to allow only very small purses and only transparent water bottles. It was 91 degrees outside, the amphitheater is outdoors, and nobody was supplying anybody with water. But we’re young people in our 20s. We made it work. I worried about some of the older folks, but I didn’t witness any emergencies.

The town hall was advertised as a masked event, but this is Indiana. I’d say only half of attendees wore masks, and nobody tried to change this. I’m inclined to cut the organizers some slack. How often does West Lafayette get somebody like Bernie Sanders? Even in 2021, it’s a big job. The amphitheater filled to capacity. People were standing in the back, and spilling around the sides.

Once you get inside, the second “wait” begins. You sit at the venue and wait for Bernie to arrive. There’s a local band (in this case we heard a group called “Stay Outside“). There’s a local politician or two, anxious to persuade voters that they really are a Berniecrat. In this case we heard from a city councilman, James Blanco. My girlfriend went to Purdue University, in West Lafayette. I remember Blanco ran on a platform of making the local buses free at the point of use:

Every time we go down there, I check to see if the buses are free. Unless you’ve got a Purdue ID, you still have to pay. These days Blanco is going to community college to become a mechanic, and he told us the budget reconciliation bill would help him do that.

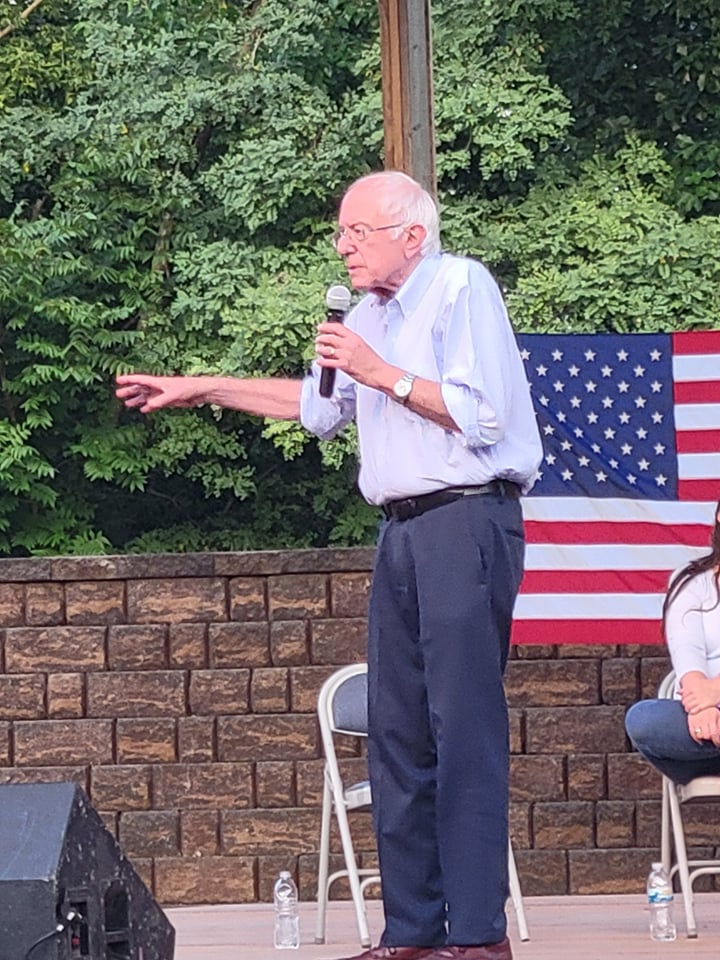

Then, at long last, Bernie Sanders arrived. At points, it felt like the good old days. Bernie went through his classic litany of facts. The top 1% own more wealth than the bottom 92%. The two richest people in the country own more than the bottom 40%. We spend more per capita on healthcare than any major country on earth. We are the only major country without paid family and medical leave. We need a Medicare-for-All single payer system. We need to make public colleges and universities tuition-free. You know how it goes.

But Bernie wasn’t here for a campaign rally. This was a town hall, about the $3.5 trillion human infrastructure bill. The Democrats are trying to pass it through budget reconciliation. It’s still being written, but is believed to have a lot of provisions:

- It makes Biden’s child tax credits permanent

- It provides three weeks of paid family and medical leave

- It makes two-year community college free

- It provides for universal Pre-K

- It subsidizes childcare

- It allows convicted felons access to food stamps

- It boosts the IRS’ budget by $80 billion over 10 years

- It spends $400 billion on in-home & community healthcare for the elderly and disabled

- It restores the top marginal rate of income tax to the pre-Trump level of 39.6%

- It spends $213 billion on building & retrofitting homes, and a further $40 billion on public housing

- It incorporates the Protect the Right to Organize Act, which would vitiate state “right-to-work” laws

- It raises the corporate tax rate from 21% to 28%, partially (but not fully) reversing Trump’s cut

- It adds vision and dental insurance to Medicare, allows Medicare to negotiate drug prices, and lowers the Medicare eligibility age

- It spends $10 billion on a “Civilian Climate Corps”

- It spends $174 billion on power stations for electric vehicles

- It spends $100 billion on energy infrastructure, with the aim of transitioning to carbon-free electricity production by 2035

This means that after Bernie tells us that we need Medicare-for-All and Tuition-Free College, he then tells us we should be excited about a bill that doesn’t do those things. There’s no headliner here, nothing you can put on a shirt or a sticker. It’s a basket of mid-tier reforms. I like many of them. I am all for relieving pressure on the housing market. I’d be happy to see the end of “right-to-work” laws.

But when I look at a suite of reforms, I ask myself two questions:

- Will these reforms help people, in the near-term?

- Are these reforms part of an effective long-term strategy to accomplish more, or are they a way of placating people?

This splits reforms into four categories:

| This reform will… | Be strategically useful | Placate people |

| Help people in the near term | Breakthrough Reform | Opiate Reform |

| Harm people in the near term | Accelerationist Reform | Villainous Reform |

Nobody should want villainous reforms. They hurt people and they make it harder for people to demand change in the future. Everybody should want breakthrough reforms. They help people and they make it easier for people to demand change. It gets difficult when we’re dealing with accelerationist and opiate reforms. These reforms involve a sacrifice, either of present for the future or of the future for the present.

Bernie says that the human infrastructure bill is the “first step” toward winning other, better reforms down the line. If that were true, it would be a breakthrough reform. But I’m not sure that’s the case. There are two provisions in the bill that I suspect are strategically counterproductive:

- The bill lowers the Medicare eligibility age

- The bill subsidizes childcare

This is not to say these provisions wouldn’t help people. Many people in their early 60s would benefit from lowering the Medicare eligibility age, and many young parents would benefit from a childcare subsidy. But I think there’s a strategic cost.

Who opposes Medicare-for-All? Older voters. Voters over the age of 65 are much less likely than younger voters to agree that healthcare is the government’s responsibility, or that healthcare should be provided through a national health insurance program. These voters are the very same people who currently enjoy access to Medicare. Once you give somebody Medicare, their personal stake in the healthcare debate diminishes.

Why didn’t we get universal healthcare in the United States in the post-war era, when so many other countries were getting it? Our government created Medicare instead. Medicare removed many of the sickest and most vulnerable people from exposure to the private insurance system. These people lost their incentive to care about whether other Americans have access to healthcare, and they lost their incentive to care about the cost of the system. This allowed our private healthcare sector to become bloated and powerful. It is now 17% of GDP, compared to just 10% in countries like Norway, Denmark, and the UK.

If we lower the Medicare eligibility age, millions of Americans will get access to Medicare, but they’ll also lose their dog in the fight for Medicare-for-All. This happens whenever we “means-test” a social program. The people who get the benefit don’t care as much if other people get it, too. The people who are excluded from the benefit resent that they’ve been left out, and this can make them more hostile to program, too. For this reason, I’m really worried about what might happen if we lower the eligibility age. It would help some people, but it would also make it harder for us to demand Medicare-for-All going forward. On my schema, this makes this specific provision an opiate reform. It helps in the near-term, but at a strategic cost.

I am also worried about the childcare subsidy. Over the past 50 years, it’s become harder and harder for parents to be stay-at-home moms or dads. In more and more households, both parents work, and if both parents are working the children don’t get much attention. This leads affluent parents to hire nannies to raise their children. It leads middle class parents to leave their kids in daycare programs. It leads poorer parents to leave their children unsupervised, to allow them to be “latchkey” kids. In all three cases, parents don’t get to raise their own children, and children don’t get to be raised by their own parents.

This was driven by wage stagnation. Over the past half-century, as real, inflation-adjusted wages have stagnated, more and more families are forced to send the second parent to work full-time. We need to correct this by increasing those wages, giving people more time and more meaningful choices about how to raise their children. Instead, this bill starts from the premise that two-income households will be the norm indefinitely. It tries to make it easier for us to permanently adopt this model by paying us to have other people raise our children. This makes it easier for us to accept a status quo we should not accept. It lowers our expectations. It is placation, by definition.

When Bernie discussed this provision, he said that in the “competitive” global economy, the world has changed. The appeal to “competitiveness” concedes that globalization and capital mobility will continue, that there’s nothing we can do about it, that all we can do is tinker around the edges to make the present situation more livable. This is not a political revolution. It’s the same kind of argument Joe Biden would make.

Big, $3.5 trillion bills don’t come around very often. A bill this size is on the table mainly because of coronavirus. We probably won’t see another spending bill this big for a while. A bill this big should contain breakthrough reforms, the kinds of reforms that will change the paradigm in the country. We need reforms that help people and encourage new debates about how we can go further and do more. Where are those reforms?

Obama-era taxes don’t cut it. Two-year community college makes life a little easier on trades workers, but there’s no reason to think it will lead to tuition-free college. Instead, it will intensify the class division between the college students who come to campus freshman year and get the whole experience, and the college students who are forced to spend their first two years at a poorly performing community college to save money. The Protect the Right to Organize Act is valuable, but big, powerful unions failed to check globalization in the 70s and 80s, when global competition wasn’t as fierce as it is today. Why would unions succeed now, in an environment where even Bernie Sanders thinks there is no alternative to the “competitive” global economic order?

Strategically, there just doesn’t seem to be a plan. After Bernie spoke, he had a few people from the community speak. One was a farmer, who invented a carbon-capture combine. Another was a young, newly elected councilwoman. There was a grad student who used the word “unhoused” instead of “homeless”. The two people who made the biggest impression were beneficiaries of the federal unemployment supplement. That program did make a big difference for poor and vulnerable people. Unfortunately, it’s ending in September, and this bill doesn’t extend it.

We finished with an audience Q&A. One brave soul told Bernie his friends were getting disillusioned, and asked him what he would say to those friends. Bernie said we should feel good, because people like Cori Bush and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have been elected to congress. Cori Bush is from St. Louis. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is from New York. Both came from bright blue districts in big cities. They don’t represent rural Hoosiers, and they don’t try to talk to them, either. The most promising young Berniecrat around is a councilman who promised free buses and failed to deliver. Even he was only elected with the support of college students in one of the handful of Hoosier towns where college students matter. The Indiana state legislature is dominated by corporate Republicans, and the Democratic opposition consists of corporate Democrats like Evan Bayh and Pete Buttigieg.

Bernie told us we had already succeeded in “raising consciousness”. It is true that more ordinary Americans support Medicare-for-All than in 2015. But nobody who cares about that issue is winning elections outside of heavily Gerrymandered Democratic safe seats. And do those people even care? Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said Medicare-for-All could just be a negotiating tactic to get a public option. She doesn’t even tweet about it:

As the rally came to a close, there was one last reminder of why I got myself involved in all of this. Bernie closed his speech by talking about basic, economic rights, the rights everyone should have, the rights we should all fight for. They were so simple and so compelling–food, water, housing, healthcare, education, energy. But there’s no strategy. I’m not sure there ever was. I think Bernie surprised himself by doing so well in 2016. What came next? Well, he wanted my generation to figure that out. And boy, have we…

What do I see when I look at Bernie Sanders in 2021? I see a kind man, a good man, a man who wants to help young people do what he himself was unable to do. But around him, I see sharks. Millennial careerists, looking to steal valor, appropriating his movement to serve their own venal ends. Their young faces make them look so innocent, but those buses? You still have to pay.