Stephen Harper’s Austerity and Weak Oil Prices are Sinking Canada’s Economy

by Benjamin Studebaker

Canada has a federal election coming up on October 19, 2015. The election could not have come at a worse time for Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s Conservative Party. Canada’s economy has ground to a halt, and the voters are furious with Harper. His net approval rating has dropped to a disastrous -32:

What has he done wrong? Let’s take a closer look.

If you don’t regularly follow Canadian politics, this is what Stephen Harper looks like:

Harper has been PM since 2006. Here’s how Canada’s growth rate has done under Harper.

You’ll notice that Canada’s growth rate has been falling since early 2015, and if it contracts again next quarter, Canada will officially be in recession. There are two key reasons why Canada is tanking:

- Oil–under Harper, Canada has focused on increasing oil production and oil exports. Oil prices have collapsed due to the increasing prevalence of fracking, and this means that economies in which oil exports play a significant role are in trouble.

- Austerity–even though he knows that oil prices have fallen and that Canada’s economy is reeling, Harper has continued to reduce government spending, further weakening the economy.

Let’s go into detail a bit about each of these.

Oil

Canada is not as dependent on oil as countries like Venezuela or Saudi Arabia, but oil makes a significant difference–it accounts for about 3% of Canada’s GDP. Canada’s oil output is almost 40% higher today than it was when Harper first became PM. Just about all of the increase in Canada’s oil production comes from Canada’s oil sands:

The oil produced by the sands is particularly expensive to extract, which means that when oil prices fall, Canadian oil is quickly priced out:

Harper has continuously tried to encourage the oil industry. He took Canada out of the Kyoto Protocol in 2011, and the IMF estimates that Canada subsidizes the oil sands industry by about $34 billion a year. In the last year, oil prices have collapsed, and this has certainly impeded Canadian growth:

The collapse will cost the Canadian government $14 billion in lost revenues this year, and the oil producing provinces’s economic numbers have been hit especially hard.

But oil is only 3% of Canada’s economy. Canada should be able to shake this off. It can’t, because the Harper government is actively undermining the economy’s performance with disastrous austerity policies.

Austerity

When consumers don’t have the money to buy goods and services, the economy grinds to a halt. Governments can help by increasing their own spending in times of need, helping to offset flagging private sector spending. They can also invest in infrastructure, technology, and education, to build an economy that is dynamic and modern.

Over the last several decades, a series of conservative and liberal prime ministers have slowly starved Canada of public investment. The right wing Cato Institute, (formerly known as the Charles Koch Foundation) lauded the move and supplies us with substantive evidence of just how much Canada has cut over the years (including all levels, federal, provincial, and local):

In 2009 and 2010, Canada wisely did a bit of stimulus to aid in recovering from the global economic crisis, and at that point Cato stopped paying attention. What happened after 2010? Harper began reducing spending again. Here’s a chart that shows just Canadian federal spending and includes some of the years after 2010 (unfortunately, Canada’s data for 2014 and 2015 is not yet available):

Harper is fond of comparing Canada’s growth rate to the other members of the G8. He points out that since 2006, Canada has outperformed most of these countries on a variety of economic indicators. What he fails to mention is that most of the other G8 countries have far more serious problems. Russia is far more dependent on oil and is currently under crippling international sanctions. Japan has a rapidly aging and shrinking workforce. Germany, France, and Italy are stuck on the euro and mired in its currency crisis. Britain has been squished by severe budget cuts since 2010. Harper is calling a tortoise “fast” because it’s won a race with a bunch of snails. Harper let the air out of his stimulus far too early. He’s been far too focused on giving Canada a budget surplus precisely when the economy needs deficit spending to keep consumption afloat. We can see this when we compare to Canada to Australia. Unlike Canada, Australia has kept its government spending quite level since the 90’s, and its stimulus was larger and longer-lasting:

As a result, after leading Australia in economic growth for many years, Canada has now fallen significantly behind:

This should not be surprising. The IMF estimates that for every 1% decrease in government spending, countries will see decreases in economic growth of at least 1%, and possibly 1.5% or higher. If citizens decide they want a smaller state, it’s one thing to reduce spending during good times, when spending cuts can help curtail inflation. These kinds of cuts may reduce public investment in infrastructure, technology, and education in the long-term, but they will do little to damage short-term growth. It’s quite another thing entirely to make spending cuts even when the economy is weak or in recession. This is precisely what Harper has done. The economic research is very clear–under current economic conditions, these cuts are wrong. They reduce living standards and damage growth rates. This relationship has held true across an array of countries:

The IMF claims that Canada’s debt to GDP ratio could climb nearly 150 points before Canada would reach its debt limit, yet Harper remains irrationally committed to reducing the size of the debt:

Says the IMF:

If fiscal space remains ample, policies to deliberately pay down debt are normatively undesirable. The reason is that for such countries, the distortive cost of policies to deliberately pay down the debt is likely to exceed the crisis-insurance benefit from lower debt. In such cases, debt-to-GDP ratios should be reduced organically through growth, or opportunistically when less distortionary sources of revenue are available.

…Reducing debt in such cases is likely to be normatively undesirable as the costs involved will be larger than the resulting benefits.

And still Harper continues to insist on running a budget surplus:

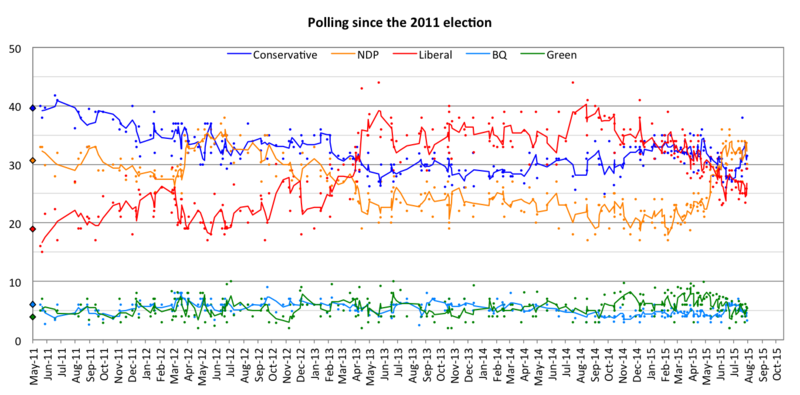

While Harper is personally unpopular, his Conservative Party remains competitive and may yet win the federal election:

With any luck, Canadians will abandon the budget surplus obsession and choose a ruling party that will make long-term investments in the economy and use stimulus spending to help counter the negative economic and social effects of the drop in oil prices. Perhaps the NDP?

BULLSHIT. Government is not flexible because it spends more than it makes and there in lies the problem, NOT in the free market, free enterprise system.

Did you actually read this?

The commentator whose mother, sadly, apparently named him “Anonymous” probably seems not to have read or understood any macro-economics texts or articles.

http://www.cfeps.org/pubs/pn/pn0601.htm

Nor is it likely Anonymous has even a glimmer of an understanding about U.S. economic history.

http://www.rooseveltinstitute.org/new-roosevelt/federal-budget-not-household-budget-here-s-why

Indeed, it would seem Anonymous hasn’t even read Benjamin Studebaker’s blog.

Pity poor Anonymous in his ignorance, but celebrate his mother’s good sense in giving him such a run-of-the-mine name to camouflage the poor soul as he stumbles erringly through life on the internet.

Well done, Benjamin! The world, alas, is full of anonymous bullshit.

Reblogged this on perfectlyfadeddelusions.

Keynian countercyclical government spending is a valid measure to counter the effect of a recession, likewise an austerity reduction in spending when the recovery is underway. Nothing odd here.

The problem comes in, when governments see the benefits of large scale government spending to win votes, and do not tail back the spending when required. It is much easier to continue to spend, spend, spend. It wins you votes.

The Canadian economy just contracted and its growth rate has been falling consistently over the last year.

[…] has a federal election on October 19. Back in August, I wrote a post detailing why Stephen Harper needs to go–his austerity program and fixation on developing […]