Remember the Biden administration’s proposal to spend $2 trillion on infrastructure? Traditional infrastructure spending accounted for roughly half of that proposal. It was less than half of what the American Society of Civil Engineers believes we need. According to them, the US faces a $2.59 trillion infrastructure shortfall over the next 10 years. Now a bipartisan deal has been announced which limits new spending to just $579 billion. That’s less than a quarter of what our civil engineers believe we need. To make matters worse, the administration has agreed to fund much of the spending with public/private partnerships. Many essential infrastructure projects can’t generate a profit–they require huge up-front investments and continuous maintenance. The more an infrastructure package depends on private funding, the more limited that package is in the kinds of projects it can fund. How did it come to this? Let’s run through some of the reasons why the infrastructure plan was so completely butchered.

As I see it, there were four main obstacles to a suitable infrastructure bill:

- Disagreements over what legitimately counts as “infrastructure” spending

- Disagreements over how to pay for infrastructure

- Inflation fears

- Dysfunctional political institutions

Let’s say a bit about each.

What Counts as “Infrastructure” Spending

The Democrats decided to pack the infrastructure bill with a lot of other spending. $400 billion alone was slated to go to nursing home services, a pressing need in its own right, but not one of the needs which the American Society of Civil Engineers tracks in its reports. We need to spend $2.59 trillion in the next decade on pure, traditional infrastructure. By including so much other spending in the initial bill, the Democrats made the bill appear corrupt, bloated, and untrustworthy. Republicans took advantage, framing the bill as a mystery box of liberal giveaways.

The Biden administration made this problem worse by disparaging traditional infrastructure. In March, a Washington Post story included this damning line:

Some people close to the White House said they feel that the emphasis on major physical infrastructure investments reflects a dated nostalgia for a kind of White working-class male worker.

The idea that only white men benefit from traditional infrastructure spending is absurdly bigoted. American citizens of every background are employed in industries which benefit from infrastructure spending. American citizens of every background need functioning infrastructure. When the ASCE says we need $2.59 trillion for infrastructure, they’re saying that if we don’t get that money a substantial amount of infrastructure will fall into disrepair. We cannot have a functioning country without functioning infrastructure. To frame it as a “white” or “male” concern is beyond preposterous.

What’s more, it was deeply politically stupid. By framing traditional infrastructure as suspect, the White House sent a message to blue collar voters that this package isn’t really concerned with helping them. It’s not as if the White House has a blanket policy of opposing nostalgia for the 20th century. The administration loves comparing Joe Biden to FDR, and COVID stimulus to the New Deal. But it won’t countenance nostalgia for Dwight Eisenhower’s interstate highway spending, because that might actually get some Republican voters excited about the bill. If the administration wants Republicans to support this bill, they should be framing infrastructure spending in a manner that is attractive to Republican voters. Biden should have been publicly comparing himself to Ike. The bill should have consisted overwhelmingly of the traditional infrastructure spending the ASCE says we need. If Biden had promised $2 trillion in straightforward infrastructure spending over the next 10 years, he would have deprived Republicans of their best argument against the bill. He would have created enormous excitement in ordinary people.

The failure to do this instead created a cloud of suspicion around the bill from the very beginning.

How to Pay for Infrastructure

The Democrats decided to partner the infrastructure proposal with a plan to raise corporation tax. The Republicans, of course, took this as an attempt to gut Donald Trump’s tax cuts. This made the infrastructure plan appear to be a device for raising taxes, and that shifted the argument. Instead of talking about all the cool traditional projects we could fund with the spending package, we got into a grim argument about whether companies can handle a tax hike as they emerge from the pandemic.

Infrastructure spending is not permanent. This was a one-off spending bill, and it didn’t need to be costed as if it were going to be a permanent entitlement or liability for the federal government. The bill could have been framed as a growth measure, to revitalize the country after many years of slow, plodding development. The economy is still well below the trend line that developed in the years leading up to COVID. It’s still below the trend line that developed in the years leading up to the global economic crisis of 2008. Outdated infrastructure is a drag on growth. By updating our infrastructure, we could unlock a lot of untapped potential. Biden could have pitched this spending program as new hope for a country that’s badly in need of a unifying, positive narrative.

Instead, he partnered it with tax increases, and that put elites on the defensive. The most powerful businesses in the country are transnational corporations, with footprints all over the world. Those companies don’t rely principally on American infrastructure. They don’t really care if our infrastructure improves, if our living standards rise. They are much more interested in protecting themselves from tax increases. By tying these two issues together, Biden triggered a lot of powerful interest groups to oppose the package.

If the administration really has its heart set on raising taxes right now, it should do it not to fund one-off infrastructure spending but to fund permanent programs that clearly transfer funds and resources to ordinary Americans. When tax increases are tied to permanent programs, voters can look at how those programs will benefit them. They can make the argument that the benefits are worth more than the costs. Infrastructure’s benefits are big picture. They cannot be reduced to a specific number of dollars that the ordinary American will receive or save.

The right was able to tell the American people that a tax hike might cost them their job. They were able to tell the American people that the infrastructure spending was in truth a grab bag of liberal pork. Suddenly, instead of a source of hope, the infrastructure program looks like just another corrupt policy that might result in layoffs.

Inflation Fears

Over the last couple months, inflation has finally started to rise a bit. As I write, it’s now around 5%. This led to a lot of Republican worries about hyperinflation, and it made Republicans much more reluctant to support additional spending. The fears are misplaced. The infrastructure spending bill laid out its spending over an eight year period. It did not call for $2 trillion in spending in 2022. This means that in practice, its immediate stimulus effects were pretty negligible. The main objective of infrastructure spending is to generate higher living standards down the line, in the 2030s and 2040s. Yes, some infrastructure jobs would be created over the eight years of building, but the main purpose of the projects is for them to be completed and put into service.

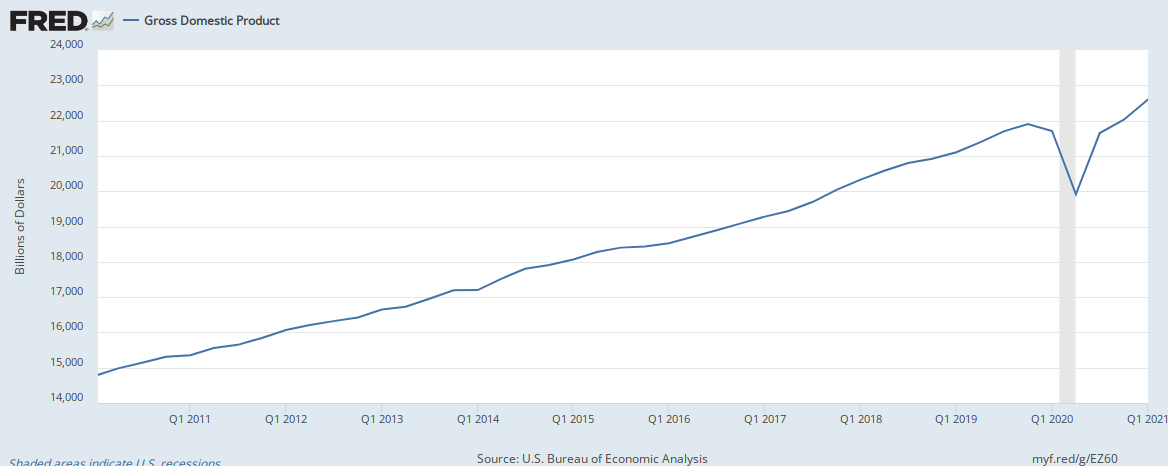

At $2 trillion over eight years, we were only talking about a potential stimulus of $250 billion per year. The US economy is still more than $1 trillion behind the level it predicted by the pre-COVID trend line:

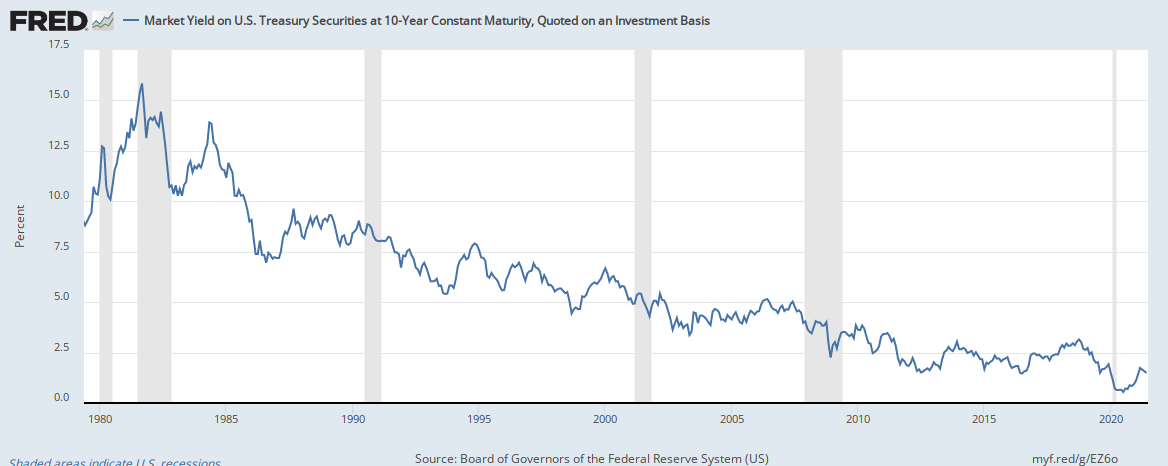

The 5% inflation we’re seeing does indicate that we’re starting to hit a growth rate that stresses the ability of the economy to meet accelerating demand. But much of this is likely down to supply chain issues that developed during COVID, rather than more fundamental capacity problems. This is clearly what the markets believe, too. Government borrowing costs remain extremely low, even as inflation has picked up:

If anything, higher inflation reduces the government’s borrowing costs. When the inflation rate exceeds the interest rate, the government is effectively being paid by the markets to borrow money.

Infrastructure spending isn’t principally a stimulus measure. It’s about the future. By immediately tying infrastructure to tax cuts, the Biden administration started negotiations by conceding a need to pay for infrastructure spending up front. Once Republican opposition to corporate tax increases was established, inflation fears drove the negotiators to look for other ways of counterbalancing the spending up front. This produced a grim political debate about who was going to pay the price for infrastructure. The longer this debate went on, the smaller the infrastructure spending became, and the more the spending was accounted for with public/private partnerships. This has dramatically reduced the number of projects the legislation will fund as well as the quality of the projects that can be funded. Private companies will only work on the projects that can predictably generate a profit, like expensive toll bridges. We need public goods, we need affordable infrastructure that everyone can use.

Dysfunctional Political Institutions

In most democracies, a working legislative majority allows the government to pass legislation. In the United States, things don’t work this way. Not only does the government need to secure majorities in both the House and the Senate, but the rules of the Senate force the government to establish a supermajority to do much of anything. This has produced a bad gridlock problem in the United States. As our problems slowly mount, neither the Democrats or the Republicans are able to experiment with policy solutions. The policies that do get passed are the result of fraught compromises. It’s never clear who is responsible for the policies that issue from the federal government, and every time anything goes wrong every part of the US government passes the buck to every other part.

This has been frustrating infrastructure for years, and the longer it frustrates infrastructure the more serious it becomes. This is not some culture war debate about what words it’s socially acceptable to use. If we cannot agree to revitalize or even maintain the basic infrastructure of the country, the country is going to literally fall into ruin.

There are two options. The first is for one of the parties to gut the filibuster and make legislation over the objections of the other. This would solve the immediate problem on any given issue, but it would also further escalate the tension between the two parties. The second is for there to be some effort made to build a new cross-party consensus. That consensus, however, would be heavily shaped by the existing elite and its rather myopic priorities.

For decades now, the parties have escalated the tension between them as a means of raising voter turnout. If the Republicans are evil, you have to show up and vote for the Democrats. If the Democrats are evil, you have to show up and vote for the Republicans. Much of this is driven by the modern primary system, which makes candidates depend heavily on the support of base voters. Nobody tries to win “swing” voters anymore. It’s all about turning out the base. Turning out the base means promising things the parties will never deliver. Policy white papers are, at this point, glorified campaign ads. These white papers also create a climate of fear and anxiety around the other party and what it might do. Both parties are treating each other’s policy white papers as if those white papers pose a real, credible threat of becoming law. Both benefit from fostering this belief. The more we think the parties mean what they say, the more we show up, both to help our party and to thwart the other one.

The truth is that at this point the gridlock is so intense that both parties can trust that very few of these policies will ever become law. This means that most of our political debate is not, in fact, political at all. It is not a debate about what policies we will enact, about what we will do with social resources. It is instead an aesthetic performance designed to agitate the American voter into feeling compelled to vote.

When a policy does slip through the cracks and becomes law, it only matters at the margins. These aesthetic performances costs very little when we are arguing over social issues that are not directly tied to the country’s ability to function. A country can ban abortion or have abortion on demand, it can ban sodomy or permit gay marriage, it can mandate masks or it can ignore them. All of these policies are consistent with having a high living standard and a functioning state.

The failure to make essential investments in the basic infrastructure of the country is not consistent with having a functioning state. Either the filibuster must go, or the primary system must go. I doubt the primary system can go, because it is heavily equated with democracy itself in the United States. Therefore, sooner or later, the filibuster will go, and internal tension will escalate further.