Political campaigns started getting expensive in the 1960s, when television advertising became the next big thing in campaigning. Even before TV, reaching people was hard work. You needed to knock on doors, phone bank, and send out mailings. All of this required a lot of dedicated activists and dedicated dollars. And so politicians depended very heavily on the activists and donors who could provide these things. All of this is in the process of changing. Activists and dollars are becoming less important than they used to be. They still matter, but not as much. And as time goes on, they grow weaker.

Every now and then, I write a blog post about an election that catches fire online. I reach several hundred thousand people, all with a post I write in a few hours. It costs me almost nothing. I don’t pay anyone to distribute the posts. People simply choose to share them. Then, because they’re being shared around, I get opportunities to write for cool magazines or be interviewed on cool podcasts. I end up being gifted platforms by other, much larger media players simply because I can generate content that resonates with people enough that they share it in significant numbers. You don’t have to spend money bribing media outlets to give you a platform if your content is attractive to their readers, listeners, and viewers. They want content that attracts an audience. You only have to spend money when your content is boring and no one really wants to look at it.

This is because social media has, to some degree, democratised the media landscape. Any person with a Facebook or a Twitter can participate in the disseminating of content. Instead of convincing one network boss to put you on the air, you can spread virally through informal social networks. Word of mouth is now electronic, and electronic word of mouth is far more powerful than the spoken variety. If you produce content that is relevant to people, eventually, it gets around. And if you know the internet well and you put effort into it, you can identify online communities that might find your work relevant and share it specifically with them. Even one person, working alone, can have a viral hit.

If you have a team of people who are experienced and skilled at using the internet in this way, it’s much easier. But for a long time, this wasn’t enough, because most people weren’t online enough. Large numbers of Americans weren’t on social media or had only a cursory presence. Gradually, this is changing–the holdouts are either being assimilated or they’re dying off. This is happening very quickly. Television news is declining year to year in a statistically visible way:

Among those under 50, the internet has long since surpassed television. Among those over 50, TV is waning:

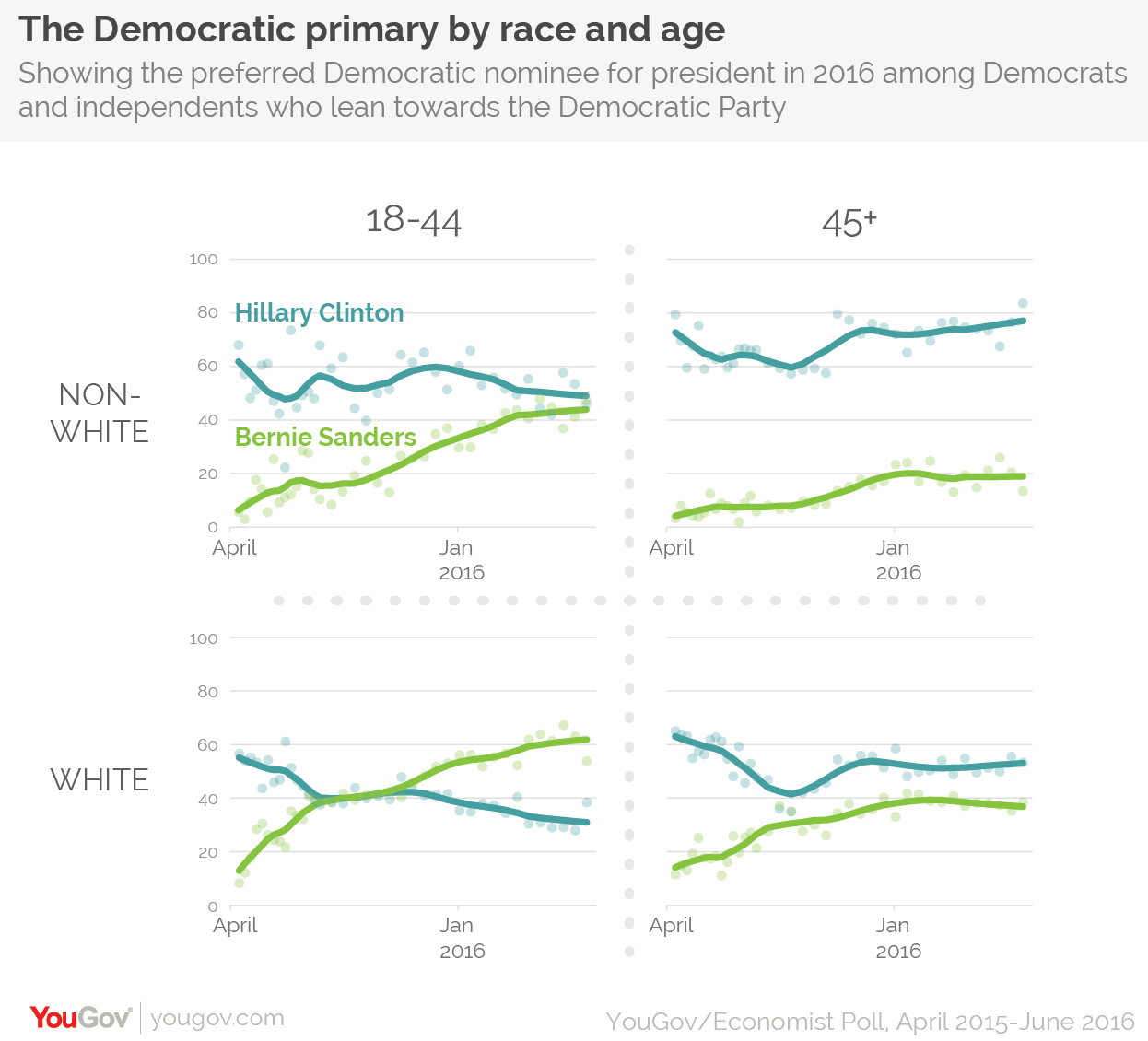

In 2016–which is now two years ago–Bernie Sanders had a clear advantage among voters who get their news from the internet rather than TV:

Every year, a noticeable demographic shift occurs in favour of the internet and against television. Television has long been the bane of grassroots campaigning. I’ve been on radio shows and podcasts and written for magazines, but nobody has ever put me on TV. Television is expensive to make, and TV networks only want to put people on whom they are confident can reach a mass audience. They’re reluctant to take a chance on someone who might only have niche appeal. They also tend to be owned by a single rich individual–like Rupert Murdoch, Michael Bloomberg, or Ted Turner–and to embody that single rich individual’s political orientation. It’s difficult to start your own TV network. It’s much easier to start a podcast or a blog, and consequently grassroots campaigns have been largely locked out of TV and therefore locked out of most Americans’ political awareness for decades.

Television reduces the public debate to a common denominator because only the common denominator draws enough eyeballs to fund television. It is a medium which necessarily shrinks and waters down the public discourse. It’s taken the internet a while to penetrate, but we may be very close now to a point where television–and consequently big money donors and media moguls–can play a much smaller role in winning campaigns. When this happens, this will fundamentally change the political calculation for candidates. It will be much more feasible to win by appealing directly to the people online.

Candidates are already starting to catch on. Donald Trump was an early adopter–he realised that if he tweeted provocative things, they’d get a lot of attention. But Trump is a septuagenarian, and while he used Twitter his ultimate goal remained procuring free TV time. The TV networks gave him time because he was so sensational that having him on would drive up their ratings. Trump was able to use the internet to leverage coverage from the traditional media players. The internet wasn’t strong enough to do all the work for him, but it played a crucial role in his media strategy.

More recently, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez defeated Joe Crowley in the New York congressional Democratic primary with a tiny fraction of the funds. Activists like to take credit, but activists work hard in a lot of failed campaigns. Ocasio-Cortez got on YouTube and made a killer video which spread like wildfire. More than 500,000 people have seen it:

Ocasio-Cortez won with 15,897 votes. 12,000 would have been enough. More than 42 people have watched her video per vote she needed to win. Imagine how many activists need to door knock and phone bank for you to reach a comparable number of people. Imagine how much money it would cost to reach a comparable number of people via TV.

It’s still the case, especially with primaries and local politics, that mailings and activists on the ground are necessary. It’s still the case, especially with general elections and national politics, that TV allows campaigns to reach millions of offline or barely online voters who are otherwise unreachable. But we’re getting closer and closer to a time when it may be possible to run a successful campaign with a few kids manning laptops in a basement. The median CNN prime time viewer is now 59 years old. The median FOX viewer is 66. Traditional media has started to report on what goes on online, and this is the first step to a new world where politics happens more online than offline, where what we collectively post on Facebook and Twitter really does become the driving force in elections.

This will make it even more important in the coming years to contest the unaccountable, absolute sovereignty Mark Zuckerberg exercises over the Facebook algorithms. Variety now reports that Zuckerberg is now partnering with TV networks to stick their content on Facebook and intends to give FOX a privileged position. If this venture succeeds, it risks undoing the political promise of the internet. Facebook’s news timetable is deeply slanted in a conservative, center-right to right wing direction:

Hopefully, no one tunes in.