It’s rarely talked about during Britain’s contemporary debate over austerity, but British austerity has a major 19th century precedent, one that ultimately culminated in the decline and fall of the British Empire.

Many may not know that the amount of debt Britain accumulated after the Napoleonic Wars was greater as a share of the British economy than the debt accumulated post-2008 or even during the World Wars:

Indeed, for much of the last three centuries, Britain’s debt burden has far exceeded its contemporary size. As you can see, the British government reduced its debt burden much faster after the world wars than it did after the Napoleonic Wars. In the 20th century, Britain’s debt burden was under 50% of GDP by the 1970’s, just three decades after the war. In the 19th century, Britain’s debt burden did not drop under 50% until around 1890, more than seven decades after the war. This means that Britain reduced its debt about twice as quickly as in the 20th century as it did in the 19th.

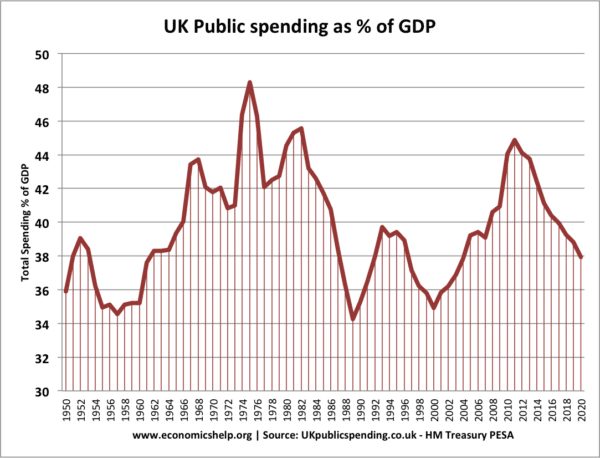

It might be natural to assume that this is because in the 20th century Britain was much more fiscally responsible. But nothing of the sort is true–following demobilization in the 1940’s, British government spending never fell to pre-war levels and increased consistently throughout the 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s, not just in absolute terms but also as a share of GDP:

The fuel was provided by the creation and expansion of the British welfare state beginning under Clement Attlee. By contrast, in the 19th century, the British government committed itself to a severe austerity plan that lasted decades. As economist Thomas Piketty describes in Capital in the Twenty-First Century:

The most interesting example of a prolonged austerity cure can be found in nineteenth-century Britain. As noted in Chapter 3, it would have taken a century of primary surpluses (of 2-3 points of GDP from 1815 to 1914) to rid the country of the enormous public debt left over from the Napoleonic wars. Over the course of this period, British taxpayers spent more on interest on the debt than on education. The choice to do so was no doubt in the interest of government bondholders but unlikely to have been in the general interest of the British people. It may be that the setback to British education was responsible for the country’s decline in the decades that followed.

Education has lagged effects on the economy–a reduction in education spending takes a couple decades to fully show up in an economy’s long-term output. This is because when a change in policy happens, the majority of people have either partially or fully completed their educations. It will take about two decades for a cohort to emerge that was not in any way influenced by previous education policy, and it will take longer still for those individuals to dominate the society’s workforce. Other European countries did not initiate massive education funding programs immediately at the end of the Napoleonic Wars–the gap in education funding grew gradually over time. There are also other areas where the British economy could have been slowed by austerity (e.g. infrastructure, healthcare, welfare spending, etc.).

But in any case, what we see in the historical record is that Britain’s relative share of global wealth peaks a couple decades after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, in the 1840’s, holding even until the 1860’s, and the dropping at an increasingly rapid pace until World War I, when Britain finally stopped the austerity. It slides further during the 1920’s when Britain tried to reimpose austerity between the wars, before stabilizing again once Britain abandons the gold standard in the 1930’s. John Mearsheimer’s figures from The Tragedy of Great Power Politics tell the story of Britain’s decline:

Britain’s huge advantage should have given it the power to suppress the industrial growth of Germany and inhibit the growth of the United States, or at least compete with it by more rapidly developing Canada and Australia. But the British state was committed to austerity and could not make the necessary investments. Even in the 1840’s at the height of British imperial power, the United States was able to threaten Britain with war, forcing it to cede the Oregon territory, which included all of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, as well as parts of Wyoming and Montana. Because Britain was committed to austerity, it was unwilling to pony up the funds necessary to defend its interests. The British Empire needed to invest in its own economic development and it needed to protect its territorial claims and industrial advantages from foreign competitors. Austerity left it powerless to do both. Eventually the result was the rise of German imperialism, two world wars, and millions of deaths. A strong British Empire could and should have prevented all of it.

What could Britain have done differently in the 19th century? It could have followed the path it followed after the Second World War. In the decades following World War II, Britain did two key things that enabled it to shrink its public debt quickly and easily without compromising public investment:

- It allowed inflation to eat away at the debt.

- It continued to invest in itself, encouraging a higher growth rate.

In the 19th century Britain stuck to the gold standard, resulting in deflation. £1 in 1815 was equivalent to £0.62 in 1900, a cumulative deflation of 38%. By contrast £1 in 1945 was equivalent to £2.70 in 1970, a cumulative inflation of 170%. This means that in the 19th century, Britain’s debt burden grew larger in real terms as time passed, causing the government to actively save large sums of money to ensure the debt and the interest were repaid. In the 20th, the debt burden grew smaller in real terms as time passed, so all the British government had to do was ensure that it did not add more to the debt than could be accounted for by inflation and economic growth.

Speaking of growth, it was much higher in Britain during the decades following World War II. In the 19th century, the Bank of England indicates that British GDP grew by around 2.07% in the 19th century. From 1948 to 1970, Britain grew by an average of 2.7%. This 0.63% may not sound like much, but over time it adds up quite a bit. If Britain had grown by 2.7% between 1830 and 1900 instead of 2.07%, Britain’s GDP in 1900 would have been about 53% higher. To give you a sense of the scale, if Britain’s per capita GDP were 53% higher than it is today, it would be almost £43,000 instead of around £28,000. That would make Britain significantly wealthier than the United States.

But alas for the empire, by the 1940’s most of the decline had already transpired, and even sound economic policy would not enable it to catch up to the US or USSR much less hold onto its remaining territories around the world. At the most critical moment, the British Empire chose to stick with austerity and the gold standard. So instead of remaining the wealthiest and most powerful nation on earth, Britain was reduced to a second rate power. Instead of investing in Britain’s future, Britain prioritized feathering the pockets of wealthy bondholders. Contemporary governments in Britain and throughout the rest of Europe have too often followed similar policies, and though we may be heartened by the possibility that modern European countries will not engage in austerity for a whole century the way that the British Empire did, even a few years of destructive policy remains destructive.

So the next time you encounter a British conservative who pines for the glory of the empire, you might remind them that it was conservative economic policy that dashed the imperial dream.