The Biden administration has come out with a $2 trillion infrastructure plan. The United States is very behind on infrastructure spending–according to the American Society of Civil Engineers, the US faces a $2.59 trillion infrastructure shortfall over the next 10 years. Biden’s bill isn’t large enough to fill that gap, and a significant percentage of its spending is for other purposes. $400 billion is slated to go to nursing home services, a pressing need in its own right, but not one of the needs which the ASCE tracks in its reports. If you add it up, it looks like roughly half the Biden bill’s spending directly addresses the needs identified by our civil engineers, while the other half funds other projects. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this–it’s very normal for politicians to attach pet programs to popular bills that meet essential needs, and many of Biden’s pet projects have value. But it does mean that this bill’s infrastructure spending is less substantial than it initially appears. It will still leave us with a significant infrastructure shortfall. The more interesting issue–and the one I wish to discuss at some length–is the decision to pair this infrastructure bill with an increase in the marginal corporation tax rate.

It makes sense to do a lot of spending when the economy is struggling, and the US economy is still, even now, about $268 billion smaller than it was in Q4 2019, before coronavirus hit. The recession also deprived the economy of the growth it otherwise would have enjoyed, and therefore something approaching a full recovery should push GDP a few percentage points above the Q4 2019 level. There’s still lots of room for growth, but we are doing better than we were doing at this point in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis:

The infrastructure bill is, however, not really a stimulus package. The spending is meant to occur over an eight year period, and therefore only a small percentage of the bill can boost GDP imminently. The justification for the bill is the long-term infrastructure investment shortfall, a shortfall which existed prior to coronavirus and which the Trump administration tried and failed to address.

The bill is not a stimulus bill, but it also does not create many permanent new programs. It is neither raising spending permanently nor injecting a stimulus–it’s a medium-term one-off investment. Permanent government spending needs to be accounted for in the budget because if the government repeatedly injects money into the economy without taking money back out again, it’s potentially inflationary. One-off stimulus spending cannot be accounted for in the budget, because if we remove the money we’re spending from circulation, the stimulus cannot have its desired effect.

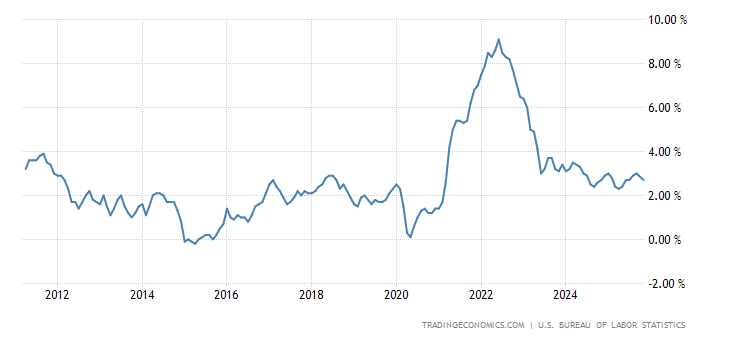

With a medium-term package like this, the government has a choice. If it raises revenue to pay for the package, this reduces its stimulus effect. If it doesn’t raise revenue to pay for the package, this might eventually contribute to a rise in inflation. How is inflation doing? So far, it’s still below target. Inflation hasn’t touched 2% since February of 2020:

The government also continues to borrow cheaply. 10 year bonds continue to trade below 2%, at rates competitive with previous lows achieved in 2012 and 2016. There’s no obvious economic reason to pay for the infrastructure package. There is, however, a non-trivial amount of potentially permanent spending in Biden’s original coronavirus relief package. For instance, Biden’s increase in child benefit will cost roughly between $100 billion and $200 billion per year. A program like that probably shouldn’t be paid for as a form of stimulus in perpetuity. But economically, there’s no strong reason to raise the funds for it now. The economy is still depressed, inflation is still low, borrowing costs are still low, and the Federal Reserve is committed to keeping them that way.

The reason to pay for this now is political. By the time the economy fully recovers, the mid-term elections will be upon us, and Biden has to worry about losing senators. If the Republicans make gains in the senate, they’ll frustrate any further effort to raise taxes. To avoid that fate, Biden is proposing a tax increase now, even though an increase right now will partially undermine the stimulus effects of this legislation, prolonging the recovery and making it more likely that when the mid-terms do come, the Republicans will gain those senate seats.

The revenue effects of the corporation tax increase are substantial, but not game-changing. If we look at the effective rate of corporation tax, the infamous Trump cut was smaller than it appears in marginal terms:

From the moment the corporation tax rate debuted, it has been effectively falling, and during the past four significant recessions (shown in dark grey on the chart), it has been cut as a form of supply-side stimulus. The Trump cut reduced it from around 16% to around 10%, but compared to the 30-40% rate achieved during the post-war era, corporation tax has long been a shadow of its former self.

A big part of the reason for the decline is capital mobility–as it has become easier for firms to move resources offshore, companies have enjoyed greater leverage over states when rates are being renegotiated. Biden hopes to restore some of the leverage governments have lost by instituting a global minimum corporate tax rate. It’s not a bad idea, but at the level Biden is proposing–12%–it would not facilitate a major increase in the rate. The Biden proposal would defend the existing rates, but it wouldn’t create an overwhelming amount of space for rate increases. The effective rate might return to the level we saw during the Obama administration, and with a global minimum of 12%, the incentive to offshore in response to the increase would be limited. But unless the minimum rate is raised considerably higher in the years to come, this will not fundamentally change the role corporation tax plays in governments’ revenue plans.

Since the corporation tax measure isn’t a gamechanger, there’s little reason to do it now, when the economy is still depressed. By presenting the infrastructure bill as an item which comes alongside a hike in corporation tax, Biden has enabled Republicans to accuse him of forcing them to choose between public and private investment. With a recession still underway, the obvious alternative is to pursue both paths at once, and to raise taxes only when the economy is fully recovered and inflation becomes a pressing concern. While it’s true that Biden may struggle to raise rates after the mid-terms, he is more likely to lose the mid-terms if he undermines the recovery with a tax hike. The hike also makes it more difficult to pass the infrastructure spending, as Republicans–and even some Democrats–are more bothered by the rate hike than they are upset by the scale of the spending.

Biden is worried about not having enough revenue to support his programs in 2023 and beyond. He should be more worried about ensuring this infrastructure bill passes and that the economy fully recovers. With a strong recovery, he could gain seats in the mid-terms and have more policy flexibility down the line. By prioritising tax hikes at this early stage, Biden shows not his willingness to break from neoliberal orthodoxy, but his insistence on continuing to follow it. He’s still more worried about bond yields and inflation than he is about growth. It’s a position that could prove very costly in the years to come. Biden should wait on the tax hike until after the mid-terms, at the very earliest. When inflation is pushing 4%, we can talk about tax hikes.

If he goes through with it, expect the hikes to slow the economy just enough for the Democrats to lose the senate. Once that happens, we’ll be back in the holding pattern we were in during the final six years of the Obama administration. That period of gridlock and plodding growth gave us Donald Trump.