As the figures for the third quarter come in, I am growing very worried about the future of Europe. Coronavirus has unleashed a disaster there that is hard to comprehend. The numbers are extraordinarily terrible. Let me show you what I mean.

I’ve put together a little chart. On this chart, a country’s level of output for Q4 2019 is “100”. So if a country is at “90”, that means that country’s GDP is 90% of what it was in Q4 2019. This allows us to see which economies have been hit hardest relative to their starting positions. I pulled the figures from FRED, ONS, and EuroStat:

The American economy lost roughly 10% of its size between Q4 2019 and Q2 2020, but it has already recovered to 96% of the Q4 level. Germany and France are keeping pace, but Britain’s “recovery” leaves it no better off in the third quarter than America was in the second. Spain’s figures are ridiculously horrifying.

To make matters worse, the European states are now in the midst of new lockdowns, and that means their Q4 2020 figures could show a return to contraction. The longer an economy operates below a peak level, the more “hysteresis” sets in. Firms that might survive a short catastrophe–especially with state aid–are increasingly forced to prepare for a new normal. They reduce capacity and that leads to permanent job losses. The unemployed are forced to spend less, and reductions in consumer spending cause more firms to reduce capacity, in a negative self-reinforcing spiral.

Sooner or later, reductions in economic output result in reductions in tax revenue, and that means states must either print money, run up deficits, or cut spending. Printing and borrowing can help fund stimulus and support economies in the near-term, but because the European countries are facing recessions that are very different in scale, different European states will recover to capacity on different schedules. Germany will likely be first to recover, and when it does it will likely view printing and borrowing as inflationary rather than helpful. When Germany’s economy is at capacity, the spending that would help other states recover would generate higher levels of inflation within Germany. It’s entirely possible that Germany will have recovered to 100% of the Q4 2019 level while many European states remain depressed by 5%, 10%, or more. At that point, Germany will want to defend against inflation, and it will likely do this by pushing for spending cuts. This will strangle the recovery in the lagging states.

This is more or less what happened after 2008–Germany recovered quickly and then lost interest in pursuing pro-growth policies for other European states:

You can see how much worse 2020 is than 2008. Spain never lost a full 10% of output in 2008, but lost more than 20% in 2020. Britain, which only briefly dropped into the low 90s in 2009, fell into the 70s in 2020 and remains a full 10% in the hole.

The UK faces the double whammy of a remarkably bad coronavirus recession and the threat of Brexit contraction when its transition arrangement with the European Union expires. Britain will have more monetary flexibility than the Euro-area, but it’s unclear how far it will go. The British government recently announced an extension of its furlough program, but this program was not enough to prevent the UK from experiencing Spanish-level contraction in Q2.

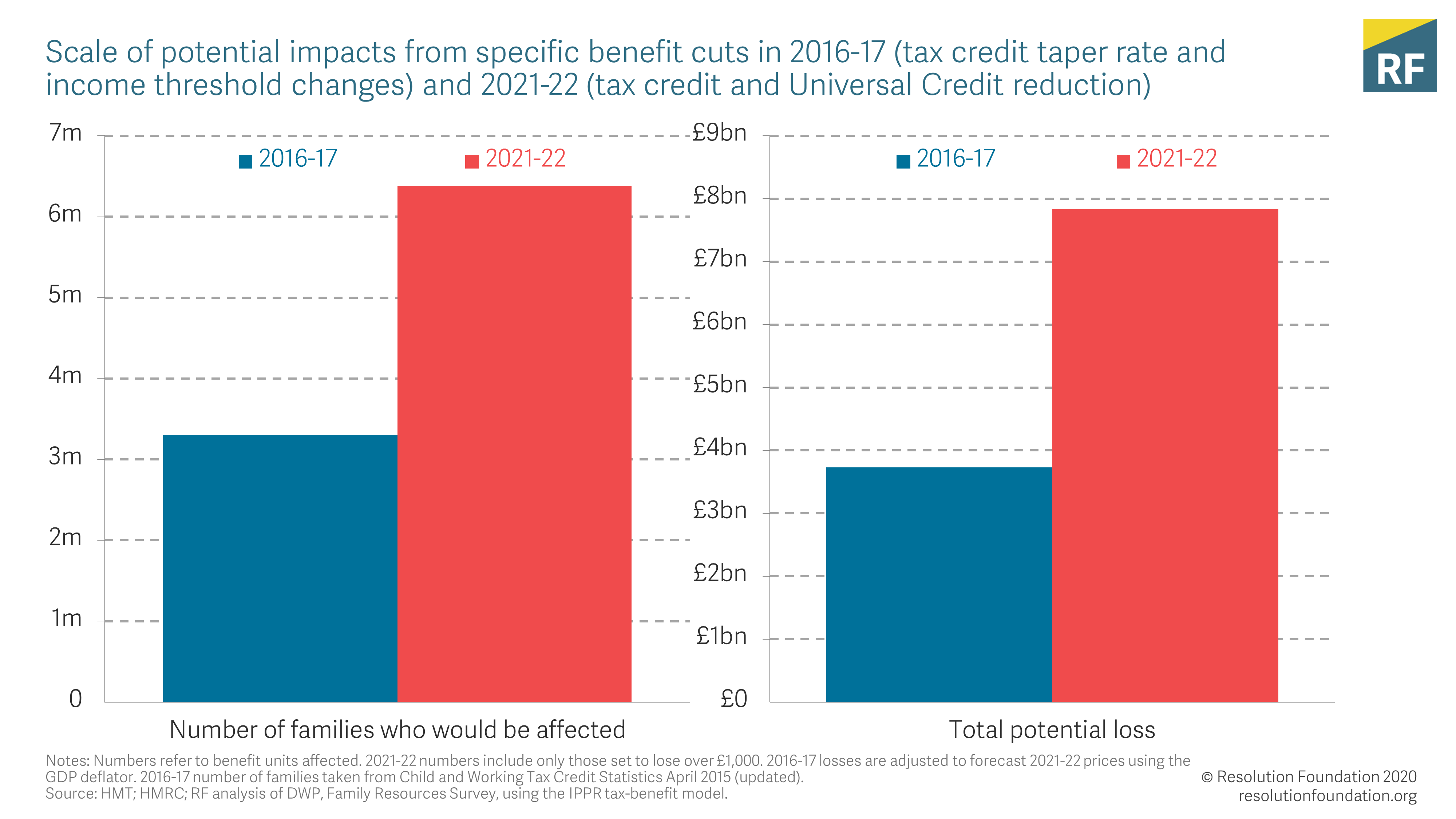

It took the government ages to realise it was necessary to extend even this insufficient program. The government still plans to go through with a massive benefit cut for the poor and vulnerable in April:

If the European countries fail to deliver on large aid packages and to maintain those aid packages through their second lockdowns and beyond, they may suffer permanent and long-lasting economic damage. Without creative and innovative aid packages, they will eventually be forced to make dramatic cuts to public services, multiplying the pain already endured in the wake of 2008.

This cannot be allowed to happen. European countries must recognize that in many cases, state aid was not equal to the task of the first coronavirus lockdown, allowing far too much contraction. As they head into a second lockdown they need to do more, not just to support the economy through the second lockdown but to make up for their lackluster response to the first. If they don’t, the widening regional inequality between core states like Germany and peripheral states like Spain will fuel nationalist sentiment and threaten to break the continent in half.

The 2010s are a dark portent for what may lie ahead. The European left was totally unable to do anything useful with the resentment created by the Eurocrisis, allowing the right to become the dominant form of anti-establishment politics on the continent. There has been no real improvement in the organization of the European left during this time, and we have every reason to think that another prolonged period of misery will aid the right.