Britain: For the Love of God, Please Stop David Cameron

by Benjamin Studebaker

On May 7 (this Thursday), Britain has a general election. I care deeply about British politics–I did my BA over there and will return to do my PhD there this fall. But more importantly, David Cameron’s government has managed the country’s economy with stunning fecklessness, and I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t do my part to point this out.

Let me tell you the story of what happened in Britain and how David Cameron made everything much, much worse.

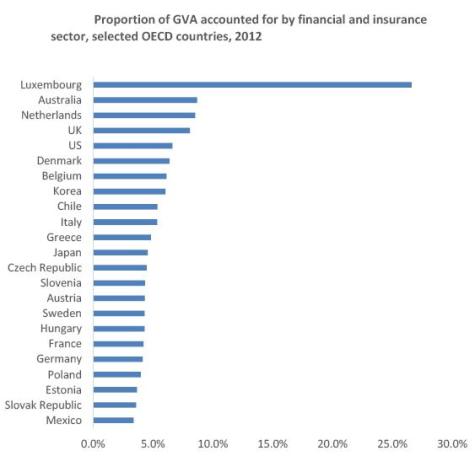

The 2008 economic crisis slammed Britain particularly hard because the UK has a big financial sector–its economy suffers heavily from “financialization”, a condition in which a lot of money is tied up in finance. In most cases, this means that not enough is flowing through the wider economy (unless you’re Luxembourg and don’t really have a wider economy). Indeed, this is a bigger problem in the UK than it is in the US:

This meant that Gordon Brown’s Labour government had to bailout a lot of banks and do a lot of economic stimulus to rescue Britain’s economy. This required it to run up the UK’s debts:

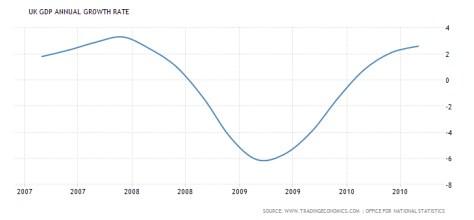

But it also prevented the UK economy from cratering, pulling it out of recession:

But British voters were in no mood to credit this recovery to Labour–instead, they blamed Labour for the recession, the bailouts, and the size of the public debt. This made no sense, because the economic crisis started in the United States because of a US housing bubble facilitated by Clinton-era deregulation of the US financial sector. But as political scientists know, the public tends to blame the sitting government for economic phenomena regardless of whether or not government policy is really responsible.

So in 2010, the British elect a coalition government led by the Conservative Party’s David Cameron. Cameron immediately begins doing austerity–he cuts government spending to in an effort to reduce the debt. The trouble is that when government spending is reduced, this cuts the legs out from under economic demand. Cameron cut benefits, salaries, and reduced subcontracts putting less money into consumers’ pockets. Here we can see the composition of UK economic growth during the Labour government as compared with that of the conservatives:

Two things stick out:

- Growth is significantly higher under Labour.

- The difference is primarily accounted for by differences in government spending.

When the conservative austerity package passed, the UK’s path totally diverged:

If we look at average annual growth rates, the UK was almost totally stagnant compared to the United States:

This experience was not unique to the UK–it quickly became clear that austerity negatively correlated with growth throughout the European Union:

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) subsequently came out with a paper stating that the multiplier (the effect of government spending on economic growth) had been massively underestimated. Then it got worse–the IMF revealed that because the multiplier is so large, austerity shrinks the economy enough to cancel out debt relief. Let me be clear–austerity reduces growth so much that it undercuts government revenue and prevents governments from shrinking their deficits. I wrote about this at the time. It was and remains shockingly clear evidence that austerity was and is failing even to reduce debt and deficits. The UK is in a significantly worse fiscal position than it was in 5 years ago:

And what did Britain have to show for it? Look at these figures:

The UK performed worse than France, a country that the Wall Street Journal accused of “descending into ridiculousness”. In the first two years, Cameron’s government put up numbers that were worse than Spain’s. Spain is a basket case–even today, Spain has an unemployment rate over 20%. Had it maintained the trajectory it was on from 2009-2010, Britain could have been doing as well as Germany in 2012.

Now, Cameron isn’t completely foolish–he slowed down the austerity after the first year:

In the first year, spending fell by about 2% of GDP. Cameron halted austerity in the second year to fight off a double-dip recession, reintroduced it at about the same pace in the third year, and then cut the pace in half for the 4th and 5th years. Consequently, Britain’s economy has started showing signs of life:

But rather than admit its error, the government now claims that these are the good results austerity was going to bring all along. This is clearly misleading–even with the growth post-2012, the UK remains behind France, and the US and Germany are still far ahead:

What the numbers really suggest is that Britain could be much further along now if it had avoided austerity to begin with. But voters have short memories, and because the British economy has been improving since the austerity slowed down, the conservatives remain electorally competitive:

To be clear, Cameron’s Conservative Party is in blue. The Labour Party is red, hard-right UKIP is in purple, the centrist liberal democrats are orange, and the hard-left greens are, obviously, green.

This is disturbing, because the Conservative Party promises to continue cutting government spending by a further 2% over the next two years if it is returned to power. This would not be as fast as the rate of cutting from 2010-2012, but it would be faster than the rate from 2012-2014. This will only serve to hinder British growth further.

According to Oxfam, the government’s austerity policies have devastated Britain’s middle and working classes in a variety of ways:

- As a result of austerity, an addition 800,000 British children will live in poverty over the next decade.

- Over the same period, 1.5 million working age adults will fall into poverty.

- By 2018, 900,000 public sector workers will have lost their jobs.

- The bottom 10% of British earners will have seen their incomes fall 38% over this government’s five year term.

Indeed, when we adjust for inflation, British workers have seen continual reductions in their wages over the course of this parliament:

And as university students should remember, the conservatives raised university tuition fees to £9,000 per year (roughly $13,600 by today’s conversion rates). This means that a British university student must now pay more to go to university than an in-state American student–for instance, Indiana residents pay only $10,388 in tuition to go to Indiana University. Before 1998, British students went to university for free. Society benefits from a well-educated population and well-trained workforce. It remains an obscene injustice to pass this cost onto young people. It deters students from pursuing degrees, particularly those degrees that are less financially lucrative.

In sum, this austerity serves no economic purpose–its exists because the Conservative Party wants to cut the welfare state so it can reduce taxes on the rich and for no other reason.

The Labour Party has done a bad job of attacking austerity–indeed, it promises to prioritize cuts as well. There are however two key differences:

- Instead of cutting the deficit 2% over 2 years, Labour promises to eliminate the deficit a little bit at a time each year, which implies a cut of about 0.4% per year for five years–this is not good for the economy by any means, but it is less bad than a quick 2% cut.

- The composition of the cuts will be different. The conservatives promise to avoid increasing most taxes, and some they even plan to cut (including inheritance tax, which targets the wealthy and affluent). This forces the conservatives to make deeper cuts to benefits and to the welfare state to achieve their budgetary goals. Labour promises to raise taxes on the rich, which will offset cuts in other areas and facilitate a decrease in tuition fees from £9,000 to £6,000.

This is not by any means an ideal alternative–Labour has done little to combat the Conservative Party’s narrative that the debt poses an existential economic threat to the UK. Austerity is not an effective way to fight debt, but Labour has not challenged this claim and as a result it has become part of what ordinary British voters consider common knowledge. As a result, it has become impossible to be taken seriously in British politics if one does not promise significant spending cuts. Even the Greens are promising to focus on the debt, though their manifesto calls almost exclusively for tax increases. This is remarkable, considering that UK borrowing costs are at historic lows, indicating a high level of confidence in the UK’s solvency (and a low level of confidence in its future economic trajectory):

But nevertheless, it means that for British voters, there really is no way out. They can trust Labour austerity to be less damaging for poor and working people, and they can hope that Labour will see the error of its ways and change its policies faster or more quickly than the Conservative Party would, but that’s about it. This is still significant–the UK will be better off if Labour wins–but things could be so different, if only British voters were better informed about what has been going on.

Update:

This post has gone semi-viral–it’s by far the most popular post I’ve written to date, and it’s receiving a lot of attention. As a result, it’s become impossible for me to keep up with the comments, and I know there are many places it’s being shared where I’m not around to defend it or explain the finer points. So I’ve written a follow up post, entitled 13 Terrible Tory Counterarguments, which addresses the most popular negative responses I’ve seen on the internet over the last few days. If you share Please Stop David Cameron and someone gives you grief, send them to the relevant part of Tory Counterarguments, and hopefully my response will prove adequate. As far as the comments thread here goes–there’s just too many, and if I try to do what I normally do (which is patiently respond to each and every one of you) I will not be able to keep up and will spend my whole day on the computer. I want to thank all of you for reading and sharing. Who knows, maybe it will be shared enough by May 7th that it will actually make a difference? It’s not likely, but you never know.

Interesting, well-argued and thought provoking piece, thank you.

Poorly written and riddled with inaccuracies, half truths and hand picked facts to spin a story. If a journalist wrote this we’d call it libel. Lucky you’re just a blogger.

Evidence? Your comment is straight from the Tory Head Office textbook of retorts… “if the question’s too tricky or uncomfortable… tell them to look at our track record and distract them!” Thing is, too many people are asking questions. Far more are realising the Tories are political comedians and con artists! 👎

And you are obviously conservative. They have raped the poor to enhance the rich always have and always will. No idea about the real people who keep the country going for the superrich to live total world apart lifestyles. Legal thieves is all the tories are.

There’s the poor and then there’s the people who cant afford to pay their sky bill. Such issues are not worth bringing into politics. This country is more stable than 90% of Europe. It’s the people that need to control their lives better.

Would you care to point out some of the “inaccuracies and half truths” – then we could actually discuss them.

Jonny you’re a troll and are probably paid to make comments like that. Your comment has no substance, nothing backing up your claims of “riddled with inaccuracies”. Name them, them maybe your comment would be worth something.

Dick

Economists from all over the world have stated austerity does not work. What more do you need to know?

You don’t back your diatribe with any facts, but there is a wealth of data supporting the content of this article.

A very well put together piece full of socialist accounts and Pro European facts and figures let’s not forget when Cameron took over there was no money left Labour had spent up after wasting Billions of Tax payers money and I’m no Tories Verdict highly Inacurate view

Fair point. Please describe how the graphs demonstrating equal spending between Blaire and Thatcher’s governments can be interpreted as Labour wasting billions. Then explain what “no more money left” means when Studebaker has shown how Britain has never been close to having no money. Honestly, just read and understand first, then dismiss it if you can.

You obviously haven’t got a girlfriend,way to much time on your hands.

A typical ignorant and childish jibe. This country needs more people like him. If so, maybe we’d all be in a better place.

More people to type their opinions on the internet? The UK needs that like I need a chocolate teapot.

The internet is a place to debate, what else is it for you moron

said the man who came here to post a petty insult

said the man who can’t spell ‘Penis’.

haha nicely pointed out.

So much to take in and beleive in ,is labour a gamble worty taking ?then again who brought in the dreaded bedroom tax ,certainly not by someone living in our world ,imigration gone stupid ,ministers cheating the system (2 homes and claiming) Think i ll risk a change goforit !!!!!!!!!!

The bedroom tax is 100% justified.

I have made this point for years. What I have always found surprising is that members of the Labour Party have never defended Gordon Brown’s intervention in the crash nor Alastair Darling’s cautious infrastructure investment programme in the immediate aftermath. I find it bizarre that for the last 5 years they have just taken the punches and allowed the Tory rhetoric that Labour can’t be trusted with the economy to be amplified.

Here, here! The slip up that Gordon Brown made in his Commons speech has proven to be true – he did save the World!

They. Ant be trusted, Gordon Brown deregulated the city when he was chancellor, he gave the keys to the prisoners!!

The mess was created over a 3 labour terms, through some of the best economi conditions that created a surplus, Labours mismanagement created the vacuum. Steering apath out has been a very calculated call, why are Geany still struggling if we got it wrong or where simply looks with timing. Look at the rate of Growth in one of you graphs for the UK , we are accelerating out not limping.

Ed balls has been quiet because he has no real plan, and can’t counter what has been achieved. Driving business and the economy, stopping the open door (not all together ) on immigration that has brought public services to breaking point is critical, investing in infrastructure and not public sector is so important.

Cameron has been curtailed by a coalition and this has diluted their affectivity. One party in power is the way forward people and not Labour.

Osborne didn’t regulate the banks. We’re as vulnerable there as ever. On the other hand, if you read Studebaker’s article you could respond to the areas where he examines the real impact of deregulation on the current situation.

We have some growth now the financial crisis is mostly over. Not as much as we could have if there had been less austerity.

Interesting article, but a bit one-sided. A couple of small observations: Perhaps tying GDP growth in with government spending is not really the best way in the long term to grow an economy. You mention at the start that the UK has a higher proportion of the economy in finance, about double Germany and France, but then make what-if comparisons throughout the article without reflecting back on the implications of that. Probably a few more points could be made, but just want to point out that Labour introduced (and raised) the tuition fee, but perhaps you forgot to mention that!

One more point, quoting Oxfam is not really a sound and objective source of ‘evidence’!

Why not?

Indeed, why not?

You should read Studebaker’s rebuttal article (the one after this) — he deals with your question. Also, in the earlier comments, about tuition fees (Labour sure ain’t perfect, austerity is worse). He does analyse the impact of deregulation, and acknowledges it had impact.

Myself, I note that Osborne has not re-regulated finance much.

This blog helps see through the pseudo economic arguments being used in this campaign.

Well researched article that makes valid points however I am curious to know why Australia, which is 2nd on the ‘financialization’ list didn’t go into recession?

Quite possibly due to their mining boom. However, with the price of iron ore now falling, they find themselves struggling and have been devaluing their own currency steadily, just so China will trade with them.

There’s one reason for the failure of the UK during 2005-2010. Labour. There’s one reason for the UK now making strong economic headway after Labour failure. Conservatives. To think, or even give credit to anything Labour did during power, is nothing short of deluded…..Irrespective of how growth should be stimulated, you can’t just rob Peter to pay Paul and not deal with the aftermath. Why have Labour remained so quiet about this? Because they hoped the Conservatives would fail to stem the flow of debt and reduce it. Instead, they succeeded.

So when do you get your next tax free windfall from Daddy’s offshore account ? You are clearly a rich Tory. Snout in the trough.

Sorry you’re too poor to take up the benefit. Guessing you’re still crying over the closed Mines and privatisation of rail.

Gordon Brown’s economic response to the crash was copied the world over. The mans an economist. Please educate yourself…

The man sold Britain’s gold supply at a record low level of worth. That’s market 101.

Yes, yes, that’s true. Oh no, actually, wait, it isn’t. My 4 month old is better with money than Gordon Brown

One reason? Wow. That is quite simplistic, you know?

Mind you, Labour haven’y exactly been idle, to still be neck-a-neck with the Conservatives in spite of loss of Scottish votes does tell you how little support the Tories really have.

Neck a neck? You obviously aren’t looking at the same polls as everyone else.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/politics/poll-tracker That one?

http://www.may2015.com/category/seat-calculator/ Perhaps this?

http://news.sky.com/election/poll-tracker Possibly that?

It’s been very close.

Interesting and well put out…..except the university piece. “British” students don’t ALL pay 9000 pounds, only those in England and Wales. Scottish students don’t pay anything like that and Im sure, they are still free for a large swathe of Scottish students.

Be careful when using “Britain” if it’s “England” you really mean

and as the parent to 3 current or recently graduated student children, most of them don’t pay up front. They just get the amount added to a nominal debt, that will hang over them for 30 years , which will get paid down slowly as a 9% graduate tax once income is above certain threshold . Come 2040 we will realise that very little of this was ever paid, its just been an accounting process to get it off the governments books.

That’s right, lower earners just have an ever increasing debt, making higher earning unattractive. Those who manage to achieve average income get a special tax that no one else has. And rich students avoid interest and pay less than everyone else. That’s not very good.

See also media macro and David Graeber

You unfortunately have no clue what you’re talking about. You’ve used statistics that omit important information and context. The prospect of anything but a Conservative government puts the fear of God into anyone who understands the situation. I’d love to join you and your friends in lefty land it sounds like a great place. But we live in the real world, with a real economy that effects real people. You shouldn’t be polluting the Internet with your misguided views. Luckily anyone with half a pea in their chumping head can clearly see you’re a massive idiot.

Wrong. Clearly you don’t live in the real world. Try living off food banks.

Well you clearly don’t live off food banks if you have the money and means to access the internet via a computer, tablet or smartphone…

I admire the thought and carefully considered arguments you put in this post. I really understand the basis of your counter to this article. Next time try bringing something tangible to the debate you pointless idiot

Sarcasm is a useless form of argument in text.

Counter-argument? No?

Yeah and so are emotional responses and childish name-calling…

Nothing says “I have nothing but empty words, void of thought or empathy to offer in this debate” better than using phrases like “lefty land”.

You clearly read the sun or telegraph as you shout ‘chaos’ but don’t have a good argument to back yourself up with. There is hard evidence that the economy has been slowing down under the conservative austerity, yet you try to claim that the conservatives are doing a good job?

I understand the situation- I do economics and the fact is our economy will not grow without investment. Also, the notion that we need to run our economy on a surplus is also a really misguided assertion that no economist ever has agreed with, the only thing is does is wins votes off people who don’t properly understand how the country manages its debt.

You have to realise that if you vote for someone because they don’t look bad eating a sandwich instead of after careful consideration of the way they have run an economy, we will get a poor government and you will have been part of the problem. The problem is with tories is you never like to admit you’re wrong, even when there is a mountain of evidence against you.

in response to the anon higher up about how “you’ve never used foodbanks if you have a computer to post that comment on” well you are wrong because having a computer and being online is compulsory if you are signing on for unemployment benefit. If you don’t have access to a computer and the internet you cannot even fill in the forms to get benefits, and you cannot apply for the compulsory number of vacancies required to continue to receive those benefits. People like you have no idea, you think the poor and unemployed should be punished, what kind of amoral/unethical upbringing did you have?

Always hearing about the Great Understanding of conservatives. Rather than being condescending, why not share some?

You can all suck my conservative dick you labor party hooligans. How do you plan to spend with Ed Milicock when you left us with no money in the kitty? Don’t any of you left loving wankers have a job to go to either? No, that’s right, you’re all too busy zooting off with your unemployment benefits designed to help real people not council trash scum bags like yourself. Get a fucking job. Earn some fucking money. Clean my fucking toilets. Do something good for the world you worthless, deluded sociopaths.

You can all suck my conservative dick you labor party hooligans. How do you plan to spend with Ed Milicock when you left us with no money in the kitty? Don’t any of you left loving wankers have a job to go to either? No, that’s right, you’re all too busy zooting off with your unemployment benefits designed to help real people not council trash scum bags like yourself. Get a fucking job. Earn some fucking money. Clean my fucking toilets. Do something good for the world you worthless, deluded sociopaths.

Well, that was worth posting twice.

and can’t spell “Labour” party either.

However much you may have used facts, I sadly feel you are too opinionated in blaming the conservatives. It is far too red and not neutral enough for me to take your arguments to heart.

I think you have got confused between debt and deficit?

I don’t. Deficit is essentially a matter of debt relative to growth. Most of our deficit exists because of recession.

This is nonsensical. What does this mean: “The trouble is that when government spending is reduced, this cuts the legs out from under economic demand.”

Where does government get the money it spends? Either from taxpayers, thus reducing demand in the first place, or debt. What makes the state a better judge of resource and spending allocation than individuals? Moreover, forcibly redistributed tax goes disproportionately into the inefficient state sector, where it will be squandered, rather than into the private sector where it will be used to boost productivity.

As a small businessman dealing with other hard working small businesses, let me tell you this: things are doing very well at the moment, jobs and wealth are being created, and the idea that things would be better under Labour is borderline offensive.

The limited economic recovery (you may be in a better recovering niche) is as a result of Tories putting the brakes on austerity after two years in government when they saw the economy tanking. In the next parliament they plan to reimplement it. Growth will be destroyed as evidenced in the collective abandoning of austerity across western countries

Growth is not built on productivity right now.

[…] You’d basically be taking ALL OF OUR MONEY and spending it on things, which is basically what George Osborne has been doing since 2012 after he realised that not spending it on things doesn’t work, but leaving that aside, your arrogant, complacent abuse of “free […]

Reblogged this on James Devine's Blog and commented:

A nice little reminder that austerity is negatively correlated with the economic growth required to pay debts.

Reblogged this on billgarnettblog and commented:

Let me tell you the story of what happened in Britain and how David Cameron made everything much, much worse…..

“This meant that Gordon Brown’s Labour government had to bailout a lot of banks”

They didn’t have to. They chose to. Gordon Browns no more boom and bust has turned into permenant bust. If we’d had a proper collapse in asset values, then we’d be in a proper recovery now. As Von Mises said:

“There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion. The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as the result of voluntary abandonment of further credit expansion, or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency system involved.”

All political parties are pushing never ending credit expansion which enriches asset holders at the cost of workers. They’ll keep doing it until the whole system falls over.

This article should be used to inspire someone to spin a one sided story into propaganda for the Labour party. You are not even living in England. So how can you see how our working class live (When i say working class i don’t mean those on benefits). Has everyone forgotten what it was like when Labour were dealing with the economical crash. I honestly thought Gordon Brown had been smuggled into our government by communists.

Many of those that claim benefits are working. Child tax credits, tax credits, low pay, part time and zero hour contracts.

You honestly thought that about Gordon Brown? If you mean it literally, it sounds pretty paranoid. I remember how the Coalition took on a growing economy.

Reblogged this on On wishes and horses and commented:

Third party interprets the numbers for voters who simply don’t get it.

Thank you for your informed perspective that helps puts some facts and figures around what many of us experience as a negative development in our national culture.

You’re welcome, thanks for reading.

Very interesting read – it’s basic Keynesian economics that austerity deepens a recession, but good to see the data supports it. Also not sure if it’s possible to edit your post now but the final chart is unlabelled, which is a little confusing.

One question I have is whether there is any data suggesting a correlation between higher tuition fees and lower student enrollment at university – or rather lower enrollment from lower income families? Personally I found the student loan system quite attractive.

Oh dear! Inaccurate and very biased.

I couldn’t agree more. Clearly a one sided argument taken from the politicians kindergarten pool.

So, we are in a situation that required banks to be bailed out after 12 years of Labour rule and that was the Conservatives fault? I think you’d need to highlight exactly how that is the case in the article for it to be fully understood how by myself.

Labour supported deregulation of the banks, yes. So did the Conservatives. The article doesn’t deal with whose ‘fault’ the financial crisis was, but rather how in the aftermath of the crash Labour’s policies increased growth, and once the coalition took power and started austerity measures, growth was significantly reduced.

The point being austerity doesn’t reduce debt burden.

This isn’t even particularly a party-political issue since Labour also plans to continue making cuts, just at a lesser rate than the Conservatives.

[…] either case, austerity will live on and our economy will stagnate with normal people feeling the pinch as the financial institutions and multinational corporations […]

You can’t just link changes in GDP growth to levels of government spending. So many other things to consider. Of course Germany’s export heavy economy is doing better, and the US has struck gold with fracking. You might be right about austerity having a negative effect, but this article and the evidence you cite to support it is misleading

The most economically illiterate argument I have ever seen. It comes down to 2 + 2. If governments continue to spend more than they bring in they go bankrupt just like every other institution. Which is what Gordon Brown did.

And what the Conservatives have continued to do whilst stagnating the economy and hitting the poorest hardest. Try again.

The whole reason labour didn’t run a surplus under Blair and Brown, was because they were repairing the damage done to the NHS under the thatcher bitch. The whole crisis was caused by bankers (tory funders) greed and the collapse of Lehman Bros.

The tories have blood on their hands and the Lid Dems aren’t helping to wash it off.

I would rather have a Labour Gov and pay more taxes to support our welfare state and NHS.

You can’t just link gdp growth to government spending, there are so many other factors to consider. Of course Germany’s export heavy economy is doing better, and the US struck gold with fracking. The UK’s service based economy is going to take longer to recover, just as it was hit worse by the recession. You might be right about austerities negative impact on the economy, but the evidence you cite for this article is misleading.

The funny thing is – the coalition didn’t do austerity. They’re still borrowing £100bn a year to finance government spending! Calling it deficit reduction and equating deficit to ‘total debt’ is tantamount to lying. So I agree with you there.

I’d like someone to explain to me how we can spend *even more* and not call it financially foolish. They say to tax the rich, ok, how to do that? The rich are pretty adept at working around tax laws as it is, and countries which raise taxes often push tax-avoidance to new levels. Francois Holland is a case in point of what happens when you ‘soak the rich’. So that’s not a solution

Cutting the deficit is not a solution. Almost half of the tax take goes on pensions (can’t cut that, or lose votes!) and the rest gets squeezed to the point where we have no A&E which is obviously wrong, so that’s not a solution either.

We can’t cut the £60bn a year we spend on debt interest because we owe a years GDP to the financial markets, so that’s not a solution either.

The root problem is that we, in Britain, don’t actually *have* much industry that is worth anything. We have finance (great…), and services (great…) but no resources. Comparing UK to USA is like comparing an oil rich, tech rich, mineral rich vast contintent to a small post-empire backwater has-been. We don’t have any oil, little minerals, not much land and we do have an aging population and unbalanced economy. In short, we are quite screwed.

I’d be keen to hear any good ideas on how to balance the economy next term. I think instead whoever is in power will muddle through and in 20-30 years we may well have a financial implosion as the demographic timebomb of aging population / pensions hits.

http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/remember-those-killed-tory-austerity-5642530

I think that with most of these types of articles there are good things and bad things to take away from it. You make some good points, especially the start of the article which I had never thought of but there are some questionable dates/stats used that I think are there to serve your own agenda.An example would be the spending graph, of course govt spending will be higher before the recession hit than it was after, especially between 2004-2008, why wouldn’t it be. As with anything hopefully people will take it with a pinch of salt and accept it may have some useful information it it but should by no means be taken as gospel.

I find it funny when there are people commenting here that the post by Benjamin is full of errors or lies or inaccuracies ! if that is so dont just say that show proof or I can only assume your comment is just Troll work or couch coaches who actually know nothing but shout loudly so others think they do. < ( sit in any pub when football is on the screen to see them practising )

This is a very nice post. The point is well made. The one thing I would draw attention to is the figure “UK government debt to GDP” from tradingeconomics.com. The y-axis is truncated from 78-90, which, may give a false impression of the magnitude of the increase in debt to GDP ratio if one interprets bar height instead of the percentage value. This may make the difference between 78.4% and 89.4% seem much larger that 11 percentage points, given that the difference in the height of the bars is enormous. It would be clearer if tradingeconomics used a 0 – 100 y axis scale, or simply used a table.

The same data on debt to GDP ratio can be found on the ONS website data section after a search for “deficit’.

Yeah, TE formats it that way, it would not have been my choice and was not deliberate on my part.

Just adds to confusion. Search for real gdp growth in Google. Look for Eurostat, the official EU statistics organisation. They completely disagree with your stats. Who to believe?

Until a government actually tackles the blackholes that exist in so many public sector areas due to massive over employment at executive levels and not at the grass roots, by allowing those same public servants to decide on what they pay themselves now and in retirement then we might as well just consider throwing our taxes down the toilet rather than pay the HMRC.

Guy Fawkes had the right idea and its time to start again. They all have their snouts in the trough and have no understanding or are prepared to listen to how taxpayers want to see their taxes properly spent on the things that actually matter.

Whatever your politics its crazy to think you can just keep borrowing to force economic growth, if we all did that then it wouldn’t be long before we lose the roof over our head and food on the table.

We see MPs still claiming expenses to pay mortgages on 2nd homes in or around London rather than use other accommodation facilities they have at their disposal and surprise, surprise, not pay that money back when the house is sold at the end of the tenure. We see local authority chiefs using taxis to ferry themselves to ‘meetings’ less than 500 yds down the road.

Please explain why council leaders, NHS trust managers and other high ranking public sector workers are paid 3-4 times as much as the prime minister …. why they employ ex-staff as contractors at 2-3 times the pay rate than if they were employed directly …. even the BBC funded by the taxpayer has the same issues ….this craziness has to stop as its dividing society.

uk is over; England will awake from its mean spirited foreigner blaming only when they see a separate prosperous Scotland.

[…] via Britain: For the Love of God, Please Stop David Cameron. […]

Aren’t the SNP proposing the policies you advocate? An end to austerity, a modest spending increase of 0.5% to grow the economy whilst still reducing the deficit, albeit at a much slower rate than either the tories or labour.

You are a cunt

This made me chuckle. Not that I’m agreeing just hilarious in the middle of all these comments!

I have now got this spreading on Facebook and its getting people from all sides talking not arguing,which is a good thing.

Labour is no good for Scotland…..you will find on Thursday at the elections that the Scottish Nationalists will sweep the board here in Scotland.

to many people sharing very little money

selective picking of facts, economic nonsense

Without going into too much detail, I’d say some of his points are valid, but they’re very naïve and don’t actually account for the primary players/causes/drivers for any of this stuff, which isn’t governments, but is markets and central banks.

Firstly, I agree with his point that the UK recession etc wasn’t entirely the fault of Labour, there was a global financial crisis, primarily the result of a debt and credit binge supercycle that had been in place since the end of World War II (I disagree with his point that Clinton’s de-regulation of housing caused the crash in 2008), which is hardly Gordon Brown and Alistair Darling’s fault.

However, I do think it’s a bit hypocritical to shield Labour from blame for the economic crisis, yet credit them for saving the UK from the brink of collapse with their bailout of the UK banking sector (which wasn’t actually a Labour policy, the entire house of commons were faced with the decision, and there was wide cross-party agreement – would the tories/libdems/greens/ukip/whatever really have let the at-that-time biggest bank in the world RBS collapse? – I doubt it).

The real credit should be with the Bank of England, who cut interest rates, widened the window for banks to receive cash and launched £375bln of bond-buying – effectively saving the economy from deflation, debt spirals and a frozen banking sector. Then the ECB followed suit, super-easy monetary policy allowing cheaper loans, cash etc to businesses abroad, boosting biz. confidence, exports etc.

Secondly, his “in-depth” analysis of the “financialization” of the UK economy is pretty mis-guided. He states: “the UK has a big financial sector–its economy suffers heavily from “financialization”, a condition in which a lot of money is tied up in finance” What does he actually mean by this? The word finance (in this context) means the creation of money, loans and credit for the purposes of a risked return – which does the polar opposite of being “tied up” but is actually the main reason we have one of the most elastic, most diversified and most secure pools of money supply and liquidity in the world. That annoyed me. Evidence in how important our finance sector is here: http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/may/06/uk-services-pmi-hits-eight-month-high-election-boost

Thirdly – looking at annual growth rates… Why does he stop looking at the data beyond the end of 2012?

If he extended this to include Q1 2015 (THREE YEARS OF DATA MISSING) you’d see that the UK has the best growth record (better than USA) of any developed economy – with the exception of Spain and Ireland. There are crucial examples of countries that have undergone debt re-structuring, spending cuts and government overhaul – and they’re consistently the strongest performing economies on the continent today (better than Germany, Italy, France…)

Lastly, when you look at his analysis of UK real wages, we seen the same as above. Again, the data ends just before a huge upswing in real wage growth that’s a result of falling inflation as well as increasing productivity (albeit limited). He also fails to mention the best argument against the tory economic record: that despite record levels of employment and job creation, productivity per capita has collapsed – which shows our workforce is either too poorly trained, inefficiently allocated (example of this would be if Gareth Bale was a window cleaner – he’s far more productive being a footballer because of his personal talents, therefore would be inefficient at being a window cleaner) but is probably the result of pushing low paid private sector jobs on a nation that’s starved of high paid jobs (then again, better a low paid private sector job that none at all, which is what’s happening in France, Italy etc). But this really is a broader argument about secular stagnation – the theory that the global economy has hit it’s alltime peak and we’ll never EVER be as better of as we were in early 2000s.

He does discuss the more recent upswing in GDP and real wages – in relation to a slowing down of the austerity measures. Measures which will be re-implemented to a greater degree after the election – look at Osborne’s budget. A link to the last 3 years’ statistics would be helpful though.

Agree with your ‘zero-hours contract’ argument shoring up employment figures but the article was particularly about austerity.

Final point – it wasn’t an in-depth analysis of the financial sector, just an acknowledgement that a large proportion of the UK’s economy is the financial sector, and hence was hit harder by the banking collapse; but that other countries with larger financial sectors recovered more quickly without austerity.

All so true but all the options seem to be just as daunting and certainly they all lie through their teeth making ptomises that will never come to be…For the first time ever I wish ‘Screaming Lord Such ” was still around he might just have got my vote this time

Reblogged this on Psychopath Economics and commented:

This is an absolutely fantastic article on the dishonesty of the Conservative austerity drive in the UK over the last five years, and of the Tories’ insistence on continued austerity in the current general election campaign. Austerity, as with the Neoliberal enterprise generally, enriches a small elite at the direct expense of everyone else. It always has – from its first Neoliberal experiment in Chile back in 1973. It is a failure of Britain’s democracy that the truth has barely been discussed.

As I understand it, an healthy economy is one in which money circulates, from customers to businesses to wages and back into people’s purses and wallets to be spent again. People need enough in their wages to go out and spend. Businesses need to be access investment so that they can grow, especially manufacturing and the new creative industries that we are so good at starting. One reason why deficit-focussed economics is so bad for the economy is that it reduces monetary circulation and encourages low-pay (as an alternative to unemployment).

We need courage to dismiss the doom and gloom economics posited by Conservatives and their think-tank opinion-formers. Not dismissing their analysis through naïve optimism, but because monetary circulation needs to be stimulated at every level of society; those on low pay, middle-income and those who are affluent. It’s common sense. Our savings cannot be allowed to stagnate either. Raising pay (albeit gradually), investing in public services, is not wasting tax-payers money it is putting money into service.

It’s good to get a broader analysis of the bigger picture economics and realise that there is more than one ‘story’ here. Why have the Conservatives got away with peddling the myth about Labour causing the recession? I wish I knew. Perhaps in the next 5 years, the record can be set straight.

I really enjoyed your comment. It sometimes gets forgotten that money is not so much an absolute source of value as a symbol of trade, work and inter-connectivity. There is a place both for private economic activity and our collective pool represented by government spending. And at different points, each is relatively more or less important.

Reblogged this on Even Better News.

This one sided and unanswered piece of spin and the follow up comments demonstrate clearly that democracy is now dysfunctional almost beyond repair. Sad.

Thank you Benjamin. i wish the Labour Party had been saying that these 5 years

Yes, how could Labour overlook so useful and handy stats….

Oh, yeah, because they’d get ripped apart as these stats how exactly what the author wants them to show. Tories could post the same and show stats that boost there own agenda as well, but again, would get ripped apart.

I’m not a tory – but just pause for a moment and look at very basic things like the date ranges used… Why stop in 2012??? Because after that, things get better and that would ruin the authors point.

The author’s point is that when the coalition pulled back from austerity in 2012 things got better.